Author: Alexander Dugin

Translator: Jafe Arnold

Chapter 2 of Noomakhia – The Three Logoi: Apollo, Dionysus, and Cybele (Moscow: Academic Project, 2014).

***

Noomakhia and the Three Philosophical Countries

In the book In Search of the Dark Logos [1], we approached the existence of the Logoi as three views of the world or three fundamental paradigms of philosophy. We defined them as such:

- The Light Logos = the Logos of Apollo

- The Dark Logos = the Logos of Dionysus

- The Black Logos = the Logos of Cybele

These three paradigms can be provisionally placed along a vertical axis between the “here” (ενταύθα) and the “there” (εκείνα), between Earth and Heaven, between cause and effect, between the yield and the source, and so on. Each Logos builds its own universe and presents itself as the master and “demiurge.” Therefore, from a noological point of view, we are dealing not with one world but three whose paradigms conflict with one another and each encompass an infinite number of cosmic layers, hierarchies, and life cycles. It might be said that the Noomachy unfolds between these three Logoi in their vying for domination, and the reverberations of this primordial struggle are projected within these three noological universes, thus giving rise to internal battles, conflicts, splits, and oppositions. By virtue of implosion, this paradigmatic “three-way war” collapses each of the Logoi, immersing their content, structures, and “populations” into a funnel of fundamental catastrophes. Studying Noomakhia therefore demands a more careful dissection of these three Logoi. Each of them can be presented as a philosophical country, organized in accordance with certain rules with their own extended geography and topology of central and peripheral zones, and with a number of internal levels and both common and local hierarchies. These three noological countries are the country of Apollo, the country of Dionysus, and the country of Cybele (the Great Mother).

Gilbert Durand’s Three Regimes of the Imagination: The Diurne

The Three Logoi under discussion can be visually correlated with the three regimes of the imagination described in the theory of the French sociologist and culturologist Gilbert Durand [2]. We devoted a separate work to Durand and his ideas, Sociology of the Imagination: An Introduction to Structural Sociology [3], in which we rather thoroughly examined these three regimes: the diurne, the dramatic nocturne, and the mystical nocturne. Developing Henry Corbin’s central philosophical focus on the “imaginal” – that is the world of active imagination, the intermediate world between the corporeal and the spiritual, or the alam al-mithal of the Islamic tradition – Durand proposed the theory of the imaginaire, that is the “anthropological trajectory” of the structures located between the subject and object and organized in accordance with the prevalence of one or another dominant reflex. The imaginaire is structured in early childhood and later on determines the fundamental points of personality formation. Although the imaginaire necessarily encompasses all three regimes, one of them is always dominant and represses the others, thereby erecting the structure of consciousness in accordance with its own geometry and topology.

The domination of the postural reflex (which pushes the child up into the upright, vertical stance) organizes consciousness in accordance with the diurnal regime. This regime is dominated by diaeretic operations, such as division, dismemberment, the establishment of clear limits, contemplation, vertical hierarchy, severe logical laws, and is characterized by the concentration of identity towards one end (i.e., the construction of a consolidated subject) in parallel to the dissection (down to miasma) of the subject of perception at the opposite end (e.g., analyzing an object, dismembering a sacrificial animal, etc.). In the diurnal regime, the subject recognizes itself as a hero confronting time and death, with which it wages endless war. Vertical symmetries, images of flight (and fall), and masculine symbols such as the straight line, the sword, the scepter, the axis, arrows, light, the sun, and the sky are predominant in this mode. The diurnal regime fully corresponds to what we call the Logos of Apollo. This is the solar, masculine, heroic, noetic universe.

The Mystical Nocturne

The second mode of imagination, according to Durand, is completely opposite to that of the first. Durand calls this the mystical nocturne, and associates it with the nurturing reflex, with memories of the intrauterine state. When the imaginaire is captured by the structures of this mode, it perceives the world under the sign of the Night and the Mother. This regime is marked by the absence of clarity, as consciousness enjoys the continuous and unlimited tissue of hardly distinguishable things. Sensations of digestion, saturation, napping, comfort, stillness, gliding, and slight immersion are dominant. The prevailing elements are water, earth, and warmth. The relevant symbols are the cup, the Mother, twilight, reduced objects, centripetal symmetries, the infant, the blanket, the bed, and the womb. This is the feminine, maternal regime. The mystical nocturne is based on radical feminization and is an antiphrasis. In this mode, dangerous and ominous phenomena (death, time, evil, threats, enemies, and misfortune, etc.) are given softer or contradictory names:

Death = dormition (literally falling asleep) or even birth (resurrection);

Time = progress, becoming, improving;

Threat = a game resolved in peace and bliss;

The enemy = a friend who is not dangerous, and to whose side one must necessarily cross as soon as possible (Stockholm syndrome)

Misfortune = happiness (a temporary challenge designed for something good), etc.

A person with a dominant mystical nocturne is prone to seek compromise, is distinguished by conformism and hyper-conformism, is peace-loving, easily adapts to any conditions, is feminine, is drawn towards serenity, and sets comfort, satiety, safety, and harmony above all else, believing that the best is guaranteed to come naturally. Here we can unmistakably recognize the structures of the Black Logos, the noetic world of Cybele, the Great Mother, and the chthonic worlds of the womb.

The Dramatic Nocturne

The third regime of the imaginaire is also nocturnal, but is dramatic, dynamic, and active. It can be placed between the diurne and the mystical nocturne. It is built on a copulative dominant, on rhythm, movement, and dual symmetries. Its symbol is the bisexual being, the Androgyne, a pair of lovers, choreia, the circle, dance, rotation, repetition, the cycle, motion returning to its origin.

The dramatic nocturne does not struggle with time and death like the diurne, and does not cross over to the side of time and death as the mystical nocturne does. It closes time in a cycle and keeps death in a chain of births and deaths regularly replacing one another (reincarnation). In this regime, the subject is reflected in the object and vice versa, and this game of reflections is reproduced in an infinite sequence. If the diurne is the masculine regime, the realm of the day, and if the mystical nocturne is the maternal realm of the night, then the dramatic nocturne correlates with twilight (dusk and dawn) and the male/female pair (sometimes united into one). While the diurne rigidly divides one from another (diaeresis) and the mystical nocturne unites everything (synthesis), the dramatic nocturne unites the divided and divides the united – never entirely, but retaining differences in their merger and sameness in division.

Those who have a dominant dramatic nocturne exhibit developed artistic abilities, psychological flexibility, eroticism, lightness, mobility, the ability to maintain balance in motion and to perceive events in the external world as a never-ending, shifting alternation of dark and light moments (the ancient Romans’ dies fastus/dies nefastus).

Durand’s dramatic nocturne perfectly fits the description of the Dark Logos, the noetic universe of Dionysus, the god who fuses opposites in himself – suffering and dispassion, death and resurrection, male and female, high and low, and so on. Hence precisely why the “search for the Dark Logos” led us to Dionysus and the broad complex of his situation.

The Three Worlds in Mythology

Mythology, in particular Greek mythology, provides us with abundant material for composing the three noetic spaces. The realm of the Light Logos corresponds to Olympus, the heavenly world, and the king of the gods, the thunder-god Zeus, his wife, Hera of the air, the solar Apollo, the warrior Athena, the goddess of justice Dike, and other analogous figures. This is the highest horizon of the celestial Olympian gods in the maximal purity in which the Greeks tried to imagine the gods free from chthonic or archaic elements. This series of gods can be called the diurnic series, for their primary realm of rule is the that of the day, wakefulness, the clear mind, the vertical symmetries of power, and purification.

The second realm of myth, corresponding to the mystical nocturne, is that of the chthonic deities associated with Gaia, the Great Mother. This includes the “Urania” of Rhea, the deputies of the titan Cronus and the mother of Zeus, all the generations of the Titans overthrown by the gods, as well as other creatures of the Earth, such as the Hundred-Handed Ones (Hecatoncheires), the giants, and other chthonic monsters. To this category also belong some of the gods for one reason or another expelled from Olympus, such as Hephaestus. In this zone are situated the underworlds of Hades, and below it Tartarus. Here we should pay particular attention to the Titans, whose very nature reflects the characteristic attributes of the mystical nocturne. Moreover, the Titanomachy (like the Gigantomachy) can be seen as a mythological analogue of the “wars of the mind” by which we understand Noomachy. This Kingdom of Night also has its own philosophical geometry and is fundamentally opposed to that of the Day.[4] In Plato’s dialogue The Sophist, the philosophical aspect of the Gigantomachy is described in extraordinarily expressive terms:

Stranger: We are far from having exhausted the more exact thinkers who treat of being and not-being. But let us be content to leave them, and proceed to view those who speak less precisely; and we shall find as the result of all, that the nature of being is quite as difficult to comprehend as that of not-being.

Theaetetus: Then now we will go to the others.

Stranger: There appears to be a sort of war of Giants and Gods going on amongst them; they are fighting with one another about the nature of essence.

Theaetetus: How is that?

Stranger: Some of them are dragging down all things from heaven and from the unseen to earth, and they literally grasp in their hands rocks and oaks; of these they lay hold, and obstinately maintain, that the things only which can be touched or handled have being or essence, because they define being and body as one, and if any one else says that what is not a body exists they altogether despise him, and will hear of nothing but body.

Theaetetus: I have often met with such men, and terrible fellows they are.

Stranger: And that is the reason why their opponents cautiously defend themselves from above, out of an unseen world, mightily contending that true essence consists of certain intelligible and incorporeal ideas; the bodies of the materialists, which by them are maintained to be the very truth, they break up into little bits by their arguments, and affirm them to be, not essence, but generation and motion. Between the two armies, Theaetetus, there is always an endless conflict raging concerning these matters. [5]

The third kingdom, situated between Olympus and Hades (Tartarus), is the domain of the intermediate gods. The undisputed king of this mythical realm is Dionysus, who descends into Hades as Zagreus and rises to Olympus as the resurrected Iacchus of the Eleusinian mysteries and Orphic hymns. Here should also be included the psychopomp god Hermes, the goddess of harvest and fertility Demeter, as well as the countless series of lesser gods and daimons – the nymphs, satyrs, dryads, silens, etc. Some of the Olympic gods, such as Ares and Aphrodite, also gravitate towards this intermediary zone. It is also here that the titans (such as Prometheus) break through in certain situations and strive upwards. Yet the most important aspect for our sake is that it is in this mythological kingdom that we find those people whom the Orphics believed to have emerged from the ashes, or from among the titans struck down by Zeus for dismembering and eating the infant Dionysus. The nature of people is therefore simultaneously titanic and divine, Dionysian. On the upper horizon, this nature touches the realm of the daytime gods of Olympus. On the lower horizon, it descends into the underworld, the nocturnal region of the titans.

Thus, we have acquired a mythological map of the three noetic worlds of interest to us. On the basis of carefully interpreting different tropes, histories, traditions, and legends, we can glean a vast amount of data relevant to our study of Noomakhia.

Philo-Mythia and Philo-Sophia

Insofar as from the very onset we have substantiated the necessity of distance from the “contemporal moment”, we can consider the zone of myth wholly and without any reservations as a reliable basis for our quest. We can treat philo-mythia (a term coined by the Brazilian philosopher Vicente Ferreira da Silva [6]) as a parallel scholarly field alongside philo-sophia. Nothing hinders us from reversing the progression from Mythos to Logos and studying the chain from Logos to Mythos. Moreover, it would be even more productive to consider the logological and the mythological as two equal types of narratives, especially since in Ancient Greece both terms, λέγω и μυθέω, meant discourses of different semantic shades. On the level of the paradigm of thinking, as considered outside of the classical version of the historial, the equal consideration of all types of discourses is wholly legitimate. In fact, this is precisely what we see in the works of Plato and the Neoplatonists, who easily transitioned from one method to another in order to be most understandable and convincing. The “contemporal moment” demands that we approach the logological side of Plato seriously (even descending to the level of his “naive” idealism) and that we leave the mythological dimension aside, insofar as such simply reflects the “remnants and superstitions of the era.” But upon establishing distance from the contemporal moment, this whole interpretive system collapses, and we can and should turn to the Mythos and Logos simultaneously, on common grounds, in search of what really interests us.

Moreover, on the basis of the Neoplatonic language systematically developed by Plotinus, we can propose the following terminological model. The basic paradigms of thinking (and that means the sources of philosophy) are to be placed not in the realm of the Logos, but in the realm of the Nous (νοῦς) which can be seen as the common source of both Logos and Mythos. The noetic precedes the logological as well as the mythical. The Nous contains the Logos, but is not identical to it. The Logos is one specific manifestations of the Nous. The Mythos can also be considered another specific manifestation of the Nous. Therefore, they are parallel to one other on the one hand, and have a common source on the other. We are interested in precisely the noetic section, those layers of thinking and being where this divergence has not yet established. Therefore, the parallelism between philo-mythia and philo-sophia is fully justified. Noomakhia can be described and cognized both as portrayed in the picture of Titanomakhia as well as in terms of the rational polemics of philosophical schools.

With regards to the interpretation of myths and describing the relationship between the “new gods” and “ancient titans”, it is also necessary to assume a correct position from the outset. Based on the fact of the eternity of the Mind, the νοῦς (or its analogue, the spirit, the Source, etc.) as the grounds upon which all non-modern (=traditional) and non-Western (=Eastern) doctrines and religious systems are built, the diachronic structure of myth can be considered a symbolic conventionality. We ought to understand the indication that the “Titans” existed (and reigned) before the gods, sub specie aeternitatis, either as a logical continuity, or as an indication of their place in the structure of the synchronic topology of the noetic cosmos. The Titans always existed, just as the Black Logos of Cybele or the regime of the mystical nocturne. “Before” means either “higher” or “lower” depending on the viewpoint of the zone of the noetic Universe where we stand. For Mother Earth, with respect to the Titans, “before” means “better.” For the Olympians, the converse is true, since they think of themselves as the “new gods” who have won eternity in contrast to the endless cycles of the Titans’ self-closing duration. From the standpoint of the Logos of Apollo, the Titans are “ancient” because they did “not yet” know eternity, and they dwell below because they will never know it. The discrepancy between the interpretation of the “before” and “after” is not simply the consequence of relative positioning, but an episode – and a fundamental one – of the Titanomachy, which is an expression of nothing more nor less than the choice of side in the never-ending battle of eternity against time. The war of the gods and titans is a war for the position of the “observatory point”, a war to control it. Those who determine the paradigm, the grille de la lecture, will rule. We thereby find ourselves in the very epicenter of the wars of the mind. The titans seek to overthrow the gods of Olympus in order to assert their Logos as the exemplary and normative one, while the gods insist on the triumph of the diurne. Therefore, the nature of any mythical figure or account depends on from what sector of the noetic cosmos we view such, and to which army we ourselves belong. And it is this belonging to an order of one or another divine leader that Plato lays out in his Phaedrus, where Socrates explains to Phaedrus that in the person we love, we see the figure of the divine leader which our soul follows in its heavenly hypostasis. In the one we love, we love God and at the same time, in God, our higher “I.”

It would be highly naive to suppose that all people choose the camp of the gods, the Logos of Apollo and the solar regime of the heroic diurne. If this was the case, the Earth would be Heaven. Some tend towards the chthonic forces of the Earth, in solidarity with the worlds of the Great Mother. Some intuitively or consciously see themselves as warriors of the army of Dionysus. As follows, we have the right to expect from such different treatments of myths, philosophical notions, and corresponding figures of Love between the three human types.

The Geometry of the Logoi

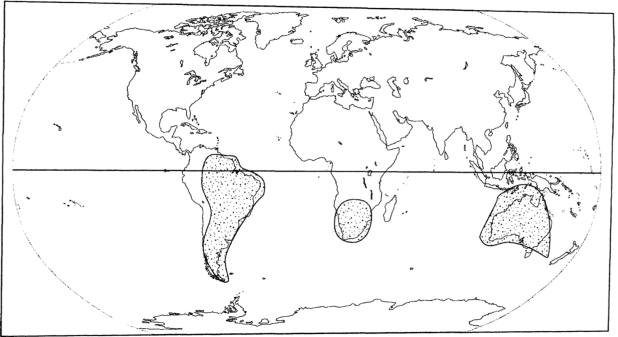

Let us imagine this picture as a whole in a diagram.

This mythological snapshot of the world can be interpreted in the most diverse ways. From a synchronic point of view, it is a map of three simultaneous regions of the world, each corresponding to the model of one of the three fundamental zones and three modes of the imagination. In this case, the Three Logoi represent three primordial positions of viewing the map of the Universe: from above (by Apollo and Olympus), from below (by Gaia, Cybele, and Tartarus), and from an intermediate position (that of Dionysus, Demeter, and humanity).

At the same time, it can be said that the basic figure of the Universe will change depending on the arrangement of this or that “observatory point.” The Logos of Apollo believes itself to be the center, the foundation, the top of the triangle or the peak of Mount Olympus (Parnassus). The view from here is a view looking down upon the base of the triangle. The descending vertical of the solar Logos sets at the opposite end of itself its opposition – the flat, horizontal Earth. Hence the Delphic formula “thou art” and “Know thyself”. The “I” is the “I” of Apollo, the peak of Olympus. And just as is the case with the path from the “I” to the “not-I”, so should the path from the “not-I” (the earthly surface, the horizontal, and expanse) to the “I” be strictly vertical (the path of the hero up Olympus). The highest point in this logological and mythological geometry is deliberately given: all the rest is positioned as away from itself, and the solar rays it emits fall to rest upon the plane of Earth. In this picture, the Earth is necessarily flat, as it is seen from the peak of the world mountain.

The intermediary world of Dionysus is structured differently. Its height rises up to the heavens and its depth reaches down to the center of hell. Dionysus’ center is in himself, while the above and below are the limits of his divine path – formed not by themselves, but over the course of the dramatic mysteries of his tragic, sacrificial death and victorious resurrection. The Logos of Dionysus is dynamic; it embodies the abundance and tragedy of life. Dionysus’ universe differs radically from the Universe of Apollo, insofar as their different views yield different worlds. The Logos of Dionysus is a phenomenon, a mutable structure of his epiphany. It is far from chaos, but it is not the fixed order of Apollo. It is a kind of playful combination of both, a sacred flickering of meanings and minds constantly threatening to plunge into madness – a madness which is healed by the impulse towards the higher Mind. It is not the fixed triangle of the mountain, but the pulsating, living heart that composes the paradigmatic canvas of thinking.

The geometry of Cybele’s Universe is completely different. On the one hand, in her we can see the inverted image of the Universal Mountain turned upside down into a sort of cosmic funnel. The symmetry between hell and heaven was vividly described by Dante. The Ancient Greeks believed that there is a black sky in Tartarus with its own (suffocating) air, its own (fiery) rivers and (foul) land. Yet this symmetry should be not merely visual, but also ontological and noological. The world of the titans consists of the refusal of the order of the diurne. The horizontal thus acquires the dimension of a downwards vertical, a horizontal of the depths. Differences fuse while identities are split asunder. Light is black, and darkness blazes and burns. If in the world of Apollo there is only the eternal “now”, then Cybele’s world is reigned by time (Kronos – Chronos), where there is everything but the “now”, and instead only the “before” and “too late”, where the main moment is always missed. The torture of Tantalus, Sisyphus, and the Danaids reflects the essence of the temporality of hell: everything is repeated to no end. The inverted triangle, as applied to the worlds of Cybele, is most akin to an inverse “Apollonian hypothesis” – and thus indeed Apollo understands this opposite to himself. Mother Earth thinks otherwise: she has no straight lines, no clear orientations. Attempts to separate one from the other cause her unbearable pain. Her thinking is muffled, gloomy, and inconsistent. She cannot break away from the mass which de-figures and repeatedly dissolves all forms, decomposes them into atoms and recreates them again at random. This is how monsters are born.

Therefore, the three views of the universe from these three positions represent three conflicting worlds, and it is this conflict of interpretations which constitutes the essence of the war of the minds.

The Philosophical Season

Looking at this model in static terms, we can also propose a kinetic interpretation. It is easily noticeable that the three synchronic worlds of this model can be taken to represent the calendric cycle: the upper half (the kingdom of Apollo) corresponds to summer, the lower world of Cybele to winter, and the intermediary worlds of Dionysus to autumn and spring. The latter can be interpreted as the cardinal points of the drama of Dionysus, his sacrificial killing, dismemberment, resurrection, and awakening. The fixed positional zones of the tripartite cosmos thus come to life and motion. The changing of the seasons becomes a philosophical process of intense thinking, a manifestation of cosmic war, in which the Logoi attack their opponents’ positions. In winter, the earth strives to swallow light, to capture the sun, and to turn flowing waters into blocks of ice. In summer comes the celebration of order, fertility, creation, and life. The cycles of the Dionysian festivities mark the key moments in this drama: the withering and the new flourishing.

The Logoi thus enter into a dialectical confrontation, the spatial topography of which is embodied in a temporal sequence. Thus, the changing of seasons is revealed to be a process of philosophizing. The natural cycle is habitually considered to be the direct opposite of history, which consists of momentary, non-repeating events. The historial manifests itself where the cycle opens – this is the axiom of “axial time.” Therefore, the symbolism of the season is seen by “school philosophy” as the direct antithesis of philosophy as such. But this axiom is valid only and exclusively from the standpoint of the “contemporal point”, a view which is only possible if we recognize historicism as a dogmatic truth. By overturning this construct in the spirit of the revolution proposed by the Traditionalists, we can propose an alternative interpretive model: history can be seen as a great seasonal cycle with its own winters and springs, and as follows, its own intersections of the ontological territories of hell and heaven. There are epochs of Apollo, Dionysus, or the Great Mother which replace one another with a certain continuity, in each of which dominates one or another paradigm, one or another Logos, one or another “philosophical season.” The eras of Apollonian rule wield an orientation towards eternity and being, towards sacred tradition and the heroic architecture of life and consciousness. These are vertical epochs, in which the cosmic fire kindles itself (Heraclitus). There is no history in these eras, there is only the event – the epiphany of constant heavenly eternity.

The era of Dionysus balances between eternity and time. It celebrates sacred time in festivals, mysteries, initiations, and ecstatic rapture. This is open time – time from which one can step into eternity. But here there is already a notable dualism between periods of joy and periods of grief (the Triterica). Half of time passes amidst the “concealment” of god, his apophenia. God dies in order to be resurrected in the Great Dionysia. He is resurrected again and resides among people (epiphany), bestowing upon them the horror and dizziness of sacred being.

The epoch of Cybele knows neither Apollonian eternity nor the ecstatic enthusiasm of the dying and resurrecting god. It is monotone and solid. It contributes to all that is gigantic and super-dimensional in a material sense but which is deprived of flight and free movement. It is in precisely this era of winter that lasting, “dragging” time is born, that which is incapable of transcendence. Here begins the reign of temporality.

Applying this theory of the philosophy of seasons to the foundational historial of modern Western philosophy, we reach an interesting conclusion. Is this “Western culture”, built on the very principle of temporo-centrism, not a sign of precisely this titanic earthly cycle? If we take into account the materialism and heightened and clearly unhealthy fixation of modern people on things and atomic (and ever more microscopic) phenomenon, the reign of quantity over quality, earthly over heavenly, and mechanical over organic, the preponderance of individualist fragmentation, including the aesthetic norms of contemporary art, then the notion that we find ourselves under the rule of the Black Logos seems to be a wholly probable supposition.

In this case, philosophy is revealed to be not a radical rupture with nature and its repetitive cycles (as the evidencia of the contemporal moment suggests), but the common, fundamental, and ontological matrix of the seasons themselves. Nature and its universal laws are thus but one form of the manifestation of the Nous and its conflicting Logoi – alongside geometry, philosophy, mythology, religion, culture, and “history.” The Nous organizes everything – both the structures of eternity and the structures of time, both natural transformations and human thinking, the trajectories of the flights of the gods and the counter-attacks of the titans. Thus, the calendar and its symbolism can by all means offer a philosophical reading. If this is a correct reading, then calendric symbolism can serve as a hermeneutic key to the comprehension of history, as has been nobly substantiated by the Traditionalist school. Guénon, Evola, and other representatives of Traditionalism univocally identified our epoch as that of the “Kingdom of Night”, the Kali-Yuga, the final age which corresponds on the synchronic, ontological map of the states of being to hell and its population. Something similar with respect to the meaning of modernity is affirmed by virtually all sacred traditions and religions. As soon as one refrains from interpreting Tradition and religion from the standpoint of the “contemporal moment”, and instead strives to determine the “contemporal moment” from the position of Tradition and religion, then everything immediately falls into place, and the anomalousness of our epoch is revealed in all of its volume. We live in the center of winter, at the bottom point of the Untergang, of descent. In this situation, it is easy to guess which Logos dominates over us, what “deities” are ruling us, and which mythological creatures and religious figures are leading today on a global scale in Noomakhia, in the wars of the mind.

The Philosophy of the First Logos: Platonism

Now we are left with pursuing the parallels between philo-mythia and philo-sophia to their logical end and proposing a systematization of the types of philosophy in terms of the mythological and seasonal maps of their paradigmatic universes. The choice of temporal sectors is more than broad enough to render this possible. However, we ought to act conventionally and therefore take as our point of departure that period which Heidegger called the “First Beginning of Philosophy”, that of classical Greece. On the basis of the synchronism of our reconstruction of the Three Logoi, we should attempt to identify three philosophical schools which to one degree or another resonate with these three corresponding paradigms.

The philosophy of the diurne, of Apollonianism, and the heroic, light ascent is, without a doubt, to be found in Plato and Platonism. Here we have the highest form of this approach, the axiomatic formulas of the vividly expressed Light Logos. Plato’s philosophy is built on the Apollonian triangle, from top to bottom, and represents the most perfect model of the embodiment of diurnic thinking. Plato himself was associated with the figure of Apollo (as was the founder of Neoplatonism, Plotinus, several centuries later). Plato was born on the day of Apollo’s festival (May 21 / Targelion 7, 428 B.C.E.) and died on the very same day in 348 at a wedding feast.[7] To this Apollonian line should be also added the ontological philosophy of the Eleatics (Xenophanes of Colophon, Parmenides, and his student Zeno), as well as Pythagoras and his school.

The structure of Plato’s philosophy meets all the requirements of the Apollonian Logos. At the top of his theory is the One, surrounded by eternal ideas. This is the peak of the divine, celestial world, illuminated by timeless light. The highest principle is the Good, which exudes its abundance firstly upon the world of ideas (paradigms) and then, through the good Creator-Demiurge, on the created cosmos. Plato described all three of these world zones in his Timaeus, in particular distinguishing the realm of paradigms (the observatory point of the gods, the Father), the realm of models, or “copies” and “icons” (the Son), and the mysterious khora (χώρα), the space or country which Plato likened to the Nurse or Mother. In describing the khora (which was later identified by the Neoplatonists with the mother), Plato’s dialogue loses its crystal clarity, thus lending towards the strange assumption that this element can be comprehended only by means of a “special Logos”, which Plato called “bastard” or “illegitimate” (νόθος λόγος) [8]. The vision of the celestial god thus reaches the surface of the earth, the lower limits of the world of copies, but here is confronted with its limits, as it can no longer see anything amenable to clear Apollonian discernment. At the border of the day, the realm of night-dreaming flickers. Timaeus (Plato) restricts himself to only a few suggestions and postulates the khora (space) to be a flat intermediary, beyond which there is nothing, and which is impossible to understand, insofar as there is nothing to properly understand in it. This khora is the view of the back of the Great Mother, a limit unreachable by the Apollonian, where hell begins. Alexander the Great, the disciple of Plato’s disciple, Aristotle, repeated the same gesture when he erected at the Caspian Gates a copper wall which symbolically closed the gateway of the cosmos (=the ecumene) to the wild hordes of North Eurasia, e.g., Scythia, which in Greek sacred geography was considered to be under the control of the titans, hence the legend that the titan Prometheus was the king of the Scythians.

The Neoplatonists extracted all possible gnoseological, ontological, and theological consequences from Plato, thus crowning the nearly millennial existence of Plato’s Academy with a complete and unique monument to Olympic, divine, heavenly thought. In a certain sense, Platonism is eternal, and has continued in both Christian theology by Clement of Alexandria, Origen, Basil the Great, Gregory of Nyssa, John of Damascus, Dionysius the Areopagite, Maximus the Confessor, Michael Psellos, John Italus, and Gemistus Plethon in the East, and by Boethius and John Scotus Eriugena in the West), as well as in the Renaissance and even amidst modern philosophy.

Aristotle: The Teacher of the “New Dionysus”

The second Logos, the philosophy of Dionysus, can be discerned in Orphism, in the teachings of the Greek mysteries (especially the Eleusinian), and manifests itself most fully in Aristotle. If hardly any doubts arise with respect to the Apollonian qualification of Plato’s philosophy, then the convergence between Aristotelianism and Dionysianism might seem, in the very least, strange and unwarranted. This is so only because Dionysus and Dionysianism are currently treated predominately through poetic, artistic, and aesthetic lenses or only with regards to the Bacchic orgies and ecstatic processes. If anything at all is established as corresponding to Dionysus, it is likely either the “philosophy of life”, biologism, or, in the worst cases, hylozoism. This means that we are not at all ready to take Dionysius seriously as a philosopher and we do not accord full consideration to his structural function in the philosophy of the world. The point is that Dionysus, on the philosophical map of the Three Logoi, belongs to the middle world below the higher paradigms, models, and ideas and above the dubious and difficult to ascertain (for the Apollonian Logos) worlds of the Great Mother. This means that Dionysus rules the world of phenomena. In this case, his philosophy should be a phenomenological philosophy. We are dealing with the notion of “phenomenon” as from φαίνω, whose root can be traced back to the meanings “light” and “reality.” The very same root is used to form aπόφασις (“concealment”), επιφάνια (“revelation”, “epiphany”), as well as λόγος αποφαντικός, which Aristotle employed to express the “declaratory expression”, the fundamental element of his logic. Dionysus is also closely associated with the cycles of “phenomena” and concealments, the rhythms of changes which compose the structure of religious life and, accordingly, the paradigm of sacred time of his adepts. But the main point is that Aristotle’s philosophy, which rethought Plato’s doctrine of ideas, discarded it, and began to construct its theories on the basis of none other than the “phenomenon” located on the border between form and matter, between μορφή and ύλη. On one side, the phenomenon rises up the divine vertical of the eidos (είδος), but unlike the Platonic idea, the eidos here is conceptualized as being closely linked to its material foundation and not outside of it. Thus, we are dealing with a genuinely “intermediary philosophy” situated strictly between the Logos of Apollo and the Logos of Cybele, one which unfolds in the zone now relinquished to the mythology (philo-mythia) of Dionysus, and which claims to have a completely autonomous structure capable of making judgements on what is higher and what is below it on the basis of its own criteria. Heidegger’s great interest in a deep, fresh reading of Aristotle was most likely inspired by precisely this clear consciousness of the fact that besides Aristotle the Logician, beyond the creator of the first ontology (metaphysics) as is customary to qualify him in the theories of the Western European historial, there is another Aristotle: Aristotle the Phenomenologist. This Aristotle tries to overcome something similar to the initiatives of Husserl and Heidegger with regrds to Plato – only not two and a half millennia after Plato, but immediately. We will attempt to illustrate this in greater detail in a separate chapter.

For now we can point out the close association between Aristotle and his royal student, Alexander the Great. According to the beliefs of devout Greeks, Alexander’s father was Zeus himself, who laid with his mother Olympia, a priestess of the cult of Dionysus, in the form of a snake (as with Persephone, the mother of Zagreus) during the Bacchic orgies, as a result of which Alexander was venerated as the “New Dionysus.” It cannot be ruled out that Alexander’s march to India was the product of his own personal faith in this astonishing tale. It is no less surprising that such an initiative – extremely difficult and dangerous in military terms – was ultimately crowned with unprecedented success, as Alexander the Great, the New Dionysus, indeed succeeded in establishing a colossal Empire which united East and West into a single cultural and civilizational space.

Another, somewhat later model of Dionysian philosophy can be discerned in the Hermetism of Late Antiquity, which represented its own kind of synthesis of fragments of Egyptian, Chaldean, Iranian, and Greek cultures with a whole number of ideas and models borrowed from Orphism and the arsenal of mysteries. Hermes, like Dionysus, was a god, but unlike many other gods was distinguished by an ontological mobility, polyformity, and the ability to rapidly and dynamically move throughout all levels of the world – from the heights of Olympus to the depths of Tartarus. The Greeks believed Hermes to be a psychopomp, the “driver of souls”, the one who drove the dead into hell and the heroes up Olympus. The philosophy that was angled around Hermes’ element was also distinct for its hybrid diversity, dynamism, and dialectical poly-semantism characteristic of the middle world. Hermetism can be seen as a shadow of Aristotelian logical phenomenology: here philo-mythia, paradigmatic qualities, the figures of the mystery cycle, and the mysterious metaphors of the planetary-mineral cycle are all employed more eagerly than the procedures of conscious reason which Aristotle and his followers would employ with such priority. The substantive difference in stylistics, however, should not hide from us the commonalities of the fundamental, paradigmatic approach of these two types of philosophizing: they belong to one and the same noological level, like two brigades of one and the same army, acting in solidarity over the course of Noomakhia. We can see this tendency towards synthesis on the part of the Hermetic spirit and Aristotelianism in the Stoa and later in the Middle Ages in Scholastic Aristotelianism (that of Albertus Magnus, Roger Bacon, and Thomas Aquinas) and in the shadow duplicated by the alchemical treatises (whether correctly or not, nevertheless tellingly) attributed to the classics of rationalist scholasticism.

The Philosophy of the Castrates

What, then, will be the third philosophy corresponding to the Black Logos of Cybele? In the solar Platonic vision, we can obtain only an external, “celestial” view, which sees as its bottom the khora (Χώρα), the space of the subtle film of the chaotic movement of scattered particles not yet formed by the ordering demiurge. Χώρα comes from the same root as mythological “chaos”, χάος, meaning “yawning”, or literally “opening the jaws”, “freeing the empty space.” Instead of the voluminous “chaos” that creates the three-dimensionality of unordered void, Timaeus sees a film that resists comprehension by the classical Apollonian logos and whose comprehension demands falling into slumber, losing clarity and rigor, and degeneration.

Aristotle paid much more attention to “matter”, ύλη. The latter becomes a necessary component of being, without which, as without the “subject” (ὑποκείμενον), there can be no being (unlike Platonic ideas, which are that which is: το ὄν). Accordingly, matter acquires a certain positive ontological dimension that is fundamentally superior to its status in Platonism. The thing as phenomenon stands in the forefront of Aristotle’s system, and all of its traits are conceived as appendices to its actual presence, the essential role in which is played by matter. As follows, in the spirit of the Logos of Dionysus we have drawn substantially nearer to the zone of matter and the Mother. It is this particular, implicit materialism in Aristotle that was taken up by the Stoics who, combining this doctrine with those of the Pre-Socratics, constructed a developed model of rationalist materialism in which even the Logos is assigned the status of a material element. The early and late Stoa (with the exception of the middle, specifically Panaetius and Posidonius, who sought to combine Stoicism with Platonism, thereby departing from the main system of this philosophy) can be considered the borderline scenario of Aristotelian philosophy, in which the center of attention is shifted to matter as its lower limit. Yet still the form, the eidos, remains the fundamental pole of the phenomenon and, as follows, therefore cannot claim the role of being the philosophy of Cybele. Instead, the latter corresponds to a different philosophical tradition, one born in the Thracian city of Abdera and transmitted from Leucippus through Democritus to Epicurus and the Epicureans, up to the Roman philosopher Lucretius Carus. This constellation of thinkers stands closest of all to the structures of the Black Logos.

Democritus built his doctrines on the complete negation of the Apollonian vertical order, thus moving not from top to bottom (as the Platonists), but from bottom to top. Democritus’ philosophy was based on two notions: the minimally indivisible particle (the atom), and emptiness, or the “Great Void.” Such is the pillar of being underlying all phenomena formed out of the interplay of atoms moving chaotically according to the laws of isonomy, i.e., in any possible direction and in any possible combination. The blind rampage of sputtered particles turns into vortices which constitute organizational ensembles, but order itself, including the eidoi, figures, bodies, and processes, is shaped by the aleatoric laws of random combinations.

Thus, Democritus argued that the gods are essentially a hallucinatory cluster of atoms and, as such, are not eternal, but are capable of appearing in dreams to inform a sleeping person of minor events or simply to frighten them. There is no harmony or immanent logic in the world, everything is utterly meaningless. Seeing the world as an insignificant accident, Democritus laughed at anyone who treated being seriously and solemnly, thus earning himself the epithet “the laughing philosopher.” Here we can see the typical depiction of the birth of Gaia as a grimacing, worm-like monster imitative of the human consciousness of a condensed phantom (εἴδωλον). The inhabitants of Abder considered Democritus to be insane. Democritus spent all of his free time – and all of his time was free, as he was a parasite living off of his inheritance – at the cemetery or in city garbage dumps. In the spirit of his general system, Democritus did not believe in eternity, the soul, or immortality, but solely in accident and the Great Void of the dead and alienated Universe.

Here we can see a vivid example of the mystical nocturne, the shift of consciousness towards the opposite side, towards identification with the blind, unseen, or ghostly forces of matter, disorder, and chaos, i.e., the philosophy of Night. Plato was completely right to see in Democritus and his atomists existential enemies, the bearers of the chthonic, titanic element. It is telling that Plotinus directly compared the atomists to the castrated priests of the Great Mother (the Galli) and emphasized that the eunuch is the only truly sterile: while woman can serve as the habitat of the ripening of a fetus, the castrate embodies ultimate vanity and absolute impotence.

Similar ideas were developed in Epicurus’ philosophy, which reduced all of reality to the sensual world and recognized the doctrine of atoms, thereby rejecting not only the being of Platonic ideas, but also the forms/eidoi of Aristotle. For Epicurus, who believed in many worlds, the gods are like perfect cohesions of atoms in complete isolation from people (between worlds) which have no influence on anything. Epicurus believed happiness to be complete indifference (ἀταραξία). Insofar as the gods are happy, they must be indifferent towards everything and, as follows, they do not participate in the life of the universe, nor the being of peoples, and therefore their presence, completely unmanifest, is essentially identical to their absence – hence the notion of deus otiosus, or the “lazy, idle god” attested in different religious and mythological systems. People are usually inclined to quickly forget such gods.

In this case, man’s soul is as mortal as his body. Epicurus believed in the evolution of species, postulating that material forces develop from the simplest forms towards the emergence of more organized beings. Moreover, Epicurus considered the goal of life to be pleasure. A full exposition of Epicurean views was presented in the poem of Lucretius Carus, who synthesized the philosophical aspects of the Black Logos with a number of chthonic myths concerned with the origins of people, the less perfect yields of the Earth which preceded them, and the forms which have not yet evolved within the span of the animal and plant world known to us.

In Democritus, Epicurus, and Lucretius Carus, we have a developed panorama of the philosophy of the Titans which shaped the Logos of the Great Mother and systematized its procedures and basic concepts. This is the intellectual headquarters of the Titanomachy active on the philosophical, religious, and cultural levels. This is one of the three main poles of the war of the minds, the Noomakhia. In this army of thinkers of the mystical nocturne, we can also see that this is not even what Gaia herself thinks, but rather the products of her parthenogenetic self-fertilization, products of her creation, mobilized into her army, generated by privation, poverty, and deficiency, i.e., the basic qualities of the material element.

The Neoplatonists saw the castrate philosophy of materialism to be a gross violation of healthy sense and related its main principles to the final four hypotheses of Plato’s Parmenides pertaining to the denial of the existence of the One. Thus, we are dealing here with a philosophy of the universe which, from an Apollonian point of view, simply cannot exist – cannot and should not.

The Relevance of the Three Philosophies

Having examined the vertical, synchronic view of the philosophical schools of classical Greece, we have divided such into three types and poles corresponding to the Three Logoi. The main figures of these three headquarters of Noomakhia are represented by Plato (and the Platonists), Aristotle, and Democritus (and Epicurus).

Platonists stand for the verticle when it exists, and they struggle for its restoration when it has been shaken. Their philosophy can change its superstructure depending on the state of the world in which the Platonist finds himself, and depending on the nature of the philosophical season. If Apollo, Zeus, and the Olympian gods hold firmly to power over the city, the people, the country, and the civilization, then Platonists act as conservatives. If Platonists are put in the context of the shifty, flickering, dramatic Logos of Dionysus or Hermes, they will be inclined towards restoration, towards raising Dionysus and preventing him from descending again. Finally, under the reality of hell, under the control of the Black Logos of the Great Mother, Platonists will fulfill the role of radical revolutionaries, philosophical extremists who challenge the suggestive magic of material lies.

Aristotelians, meanwhile, can theoretically harmoniously exist in idealist systems or accept certain positions of materialism. The Stoa demonstrates to us the limits of what is achievable.

Finally, the sensualist atomists will play the role of revolutionary nihilists in a Platonic order, and they will gravitate towards materialist interpretations of intermediary “Dionysian” systems (emphasizing the similarities between Dionysus and Hades in Heraclitus in accordance with the logic of “he went down to hell and staid there”). In the zone of chthonic culture, on the contrary, they will find themselves with the status of apologists, defenders, and guardians of the order of things.

The general system of the culture of classical Greece was built on the implicit recognition of the Olympian element and, accordingly, Apollonian philosophy (including Platonism, the Eleatics, the Pythagoreans, etc.). However, even then this trend, beyond its conservative features, bore restorationist and even partially revolutionary elements, such as in the political ideas of the Pythagorean union or the reforms which Plato proposed to the tyrant of Syracuse, Dionysus (as well as his son). To a considerable extent, they represented vanguard revolutionary projects aimed at returning full power to the solar gods who had somewhat drifted towards more mundane and less perfect powers.

After Aristotle, philosophy came to be dominated by the Stoics with their phenomenological approach and significant share of materiality (insofar as matter was considered to be the vital substance of “pneuma” and even the Logos itself). The Stoics were the first to clearly articulate the philosophy of the Empire of Alexander and then of Rome. Although atomism and Epicureanism were never dominant tendencies in classical Greece, they developed freely and drew a significant number of nocturnal minds in search of pleasure to the “philosophy of the garden.”

The Middle Ages saw Aristotelianism prevail, with both Platonism and materialism, sensualism, and atomism displaced to the periphery. In this sense, the debate on universals in Catholic Scholasticism reflected the essential sense of the Medieval balance of forces of Noomakhia: Aristotelian Thomism/Realism prevailed over the Idealism/Platonism of Scotus Erigena on the one hand and the Nominalism/Materialism of the Franciscans (Johannes Roscelin and William of Ockham) on the other.

Modernity was distinguished by the gradual rise of the Logos of Cybele. Galileo and Gassendi revived atomism, and nominalism became the basis of the scientific method. Materialism thus gradually became the criterion of scienticity. Eternity was rejected and replaced by the absolutization of time, historicism and, finally, the idea of progress. As in Epicurus’ philosophy, god first becomes “idle” (Deism) and “logical” (the “god of the philosophers”), and then yields to pure atheism (Nietzsche’s “God is dead”). The human soul is thought to be mortal and then comes to be regarded as the “psyche”, that is the sublimated continuation of the physical organism. The doctrine of the atomic structure of matter came to be laid at the foundation of the physical map of the world of Modernity, and the opening of this vacuum brings us back to the Great Void of Democritus. Space becomes isotropic and Democritus’ principle of isonymy thereby becomes dogma.

Modernity, thus, is the onset of the philosophical winter, marked by the domination of the Great Mother of Matter. The Titans storm the abode of the gods. Night triumphs over day. The mystical nocturne subjugates the ranks of the heroic diurne. Thus arises the era of the masses, of gravity (Isaac Newton’s universal gravitation) and – in René Guénon words – the “reign of quantity.” In the context of Noomakhia, this is the shift of the center of attention from the paradisal mountain to hell’s funnel, from the peak and the top to the bottom of the cosmic well. In such a situation, Platonism and its echoes, i.e., the remnants of the army of the gods, the partisans of Olympus, go underground, into the realm of peripheral mysticism, of “secret societies”, “Conservative Revolutionaries”, and “conspirators conspiring to restore the Golden Age.” In the 20th century, their programmatic manifesto was articulated in René Guénon’s books, first and foremost The Crisis of the Modern World and The Reign of Quantity and the Signs of the Times (as well as other of Guénon’s works) [9], and Julius Evola’s Revolt Against the Modern World, The Mystery of the Grail, and Ride the Tiger (as well as the rest of Evola’s oeuvre) [10].

We find the Dionysian Logos in Modernity in Hermeticism and European Romanticism, such as in Schelling’s Dionysiology or Hölderlin’s Christian Dionysianism, as well as in the many mystical circles and secret organizations which became closely interconnected in the circumstances of existence within a common underground in the face of the domination of a common enemy – the Titans. In the 20th century, this was most clearly manifested in such a phenomenon as “soft Traditionalism” (Mark Sedgwick’s term), which seeks not so much to oppose as to reconcile earthly reality with the heavenly Logos. A paradigmatic prototype of this approach can be said to be represented by the group of thinkers associated in one way or another with the Eranos seminars formed around Carl Jung, Mircea Eliade, Louis Massignon, Henry Corbin, Gershom Scholem, T. Suzuki, Karl Kerényi, and later Gilbert Durand and others. Russian religious philosophy, and primarily Sophiology, belongs to this type. In European philosophy, this current includes phenomenology, and especially Martin Heidegger. Nietzsche’s call to appeal to the figure of Dionysus was thus heard by representatives of different currents in philosophy.

Under the dictatorship of the Titans, the Logos of Apollo and the more flexible and subtle Logos of Dionysus (the Dark Logos) find themselves in a subordinate position. The main blows are dealt to direct opponents, such as Platonists, but also to representatives of the Dionysian element which, having a natural share in the Divine, are also subjected to the aggression of the sons of Earth. After all, Dionysus-Zagreus was dismembered by the Titans, and they continue to tear him apart to this day.

The synchronism and cyclical diachronism of this noological map and calendar thus allow us to discern Tradition and Modernity both as coexisting spatial zones of ontology and as successive, agonal types of domination of one or another paradigm. In the Noomachy, there are starting positions, base areas, and theaters of military operations where control over one or another height changes hands over the course of dramatic and dynamic battles. Insofar as, according to Plato, “time is the image of eternity”, time consists of both eternity’s likeness and its unlikeness. The latter consists of the diachronicity of the order of the unfolding of the philosophical seasons, of the concrete dynamics of military operations, and of the shifts in the episodes of Titanomachy (as well as the Gigantomachy and, more generally, the Noomachy). Eternity’s likeness is at its maximum at the height of Olympus, where time merges with eternity, and is at its minimal at the Great Midnight, where there is only time. This point of the Great Midnight is the culmination of Noomakhia, the moment of the Endkampf, Ragnarök, the final battle, the place and time of the Decision (Entscheidung). It is here, in the zone furthest removed from the kingdom of Zeus, in the period of the abandonment by Being (Seinsverlassenheit), during the Night of the Gods (Gottesnacht), when the gods have fled (der Flucht der Götter) and when Olympus, according to the final Oracle, has fallen, that the final mystery of Dionysus is revealed – the mystery of the only god capable of penetrating to the very bottom of hell. Heidegger spoke of the Untergehende, the one who descends into hell without being hell himself, who enters into time and is torn by it but remains, in essence, a drop of eternity. This is the heart of Dionysus saved by Athena – it is all that is left in the wake of the successful realization of the diabolical plan of the Titans.

Time prevails over eternity completely, purging it, becoming only its unlikeness, its simulacrum, a copy without an original – but only for a moment. It ceases to last once it loses its resemblance to eternity whose image it is. Of course, time denies this and tries to portray its privative being as self-sufficient. Such is the essence of the uprising of the Earth and its monsters against the dwellers of the Sky, of Heaven. The semantics of the End Times and the battle for the End Times, i.e., the battle for the “end of time”, is constituted by this proportion between autonomy and dependency.

And here it is time to remember Dionysus’ name: “The Midnight Sun.” Such is a paradox, for Night is Night because there is no sun. But where is the sun at night? Where are warmth and life during the season of philosophical winter? Where is the sky when Earth wins? Where do the gods flee? This is the question of Dionysus, his concealment, his epiphany, his essence, and his heart. This is the main question of Noomakhia.

***

Footnotes:

[1] Alexander Dugin, In Search of the Dark Logos: Philosophico-Theological Outlines (Moscow: Akademicheskii Proekt, 2012).

[2] Gilbert Durand, Les Structures anthropologiques de l’imaginaire (Paris: Borda, 1969).

[3] Alexander Dugin, Sotsiologiia voobrazheniia. Vvedenie v strukturnuyu sotsiologiiu (Moscow: Akademicheskii Proekt, 2010).

[4] Alexander Dugin, “Noch’ i ee luchi”, in Radikalnyi Sub’ekt i ego dubl’ (Moscow: Eurasian Movement, 2009).

[5] Plato, The Dialogues of Plato. Translated by B. Jowett (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1892). Russian edition: Platon, “Sofist” in Fedon, Pir, Fedr, Parmenid (Moscow: Mysl’, 1999).

[6] Vicente Ferreira Da Silva, Transcendencia do mundo (Sao Paulo: E Realizacoes, 2010).

[7] According to legend, Plato’s tomb in the Academy bore the inscription: “Apollo begat two sons, Asclepius and Plato, the one to save the body and the other the soul.”

[8] See: Alexander Dugin, Martin Heidegger: Vozmozhnost’ russkoi filosofii (Moscow: Academic Project, 2011).

[9] See: René Guénon, The Crisis of the Modern World; Ibidem, The Reign of Quantity and the Signs of the Times.

[10] See: Julius Evola, Revolt Against the Modern World; Ibidem, The Mystery of the Grail; Ibidem, Ride the Tiger.