“China in International Relations: Geopolitics, Globalization, and Hegemony”

Author: Alexander Dugin

Transcript prepared by Jafe Arnold

Lecture #4 delivered at the China Institute of Fudan University, Shanghai, China, December 2018 [VIDEO]

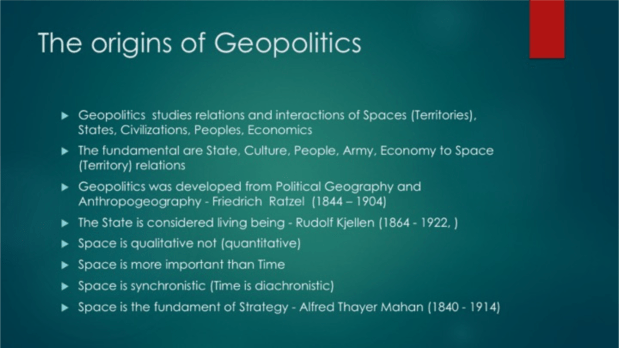

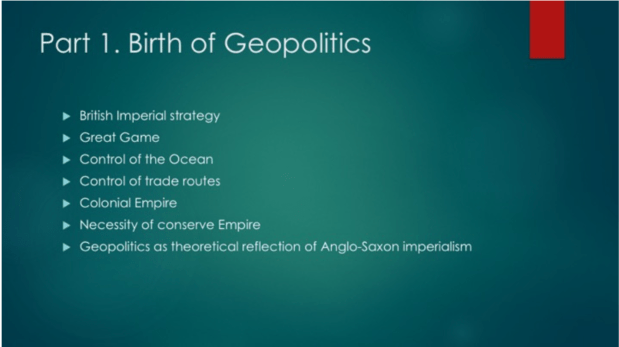

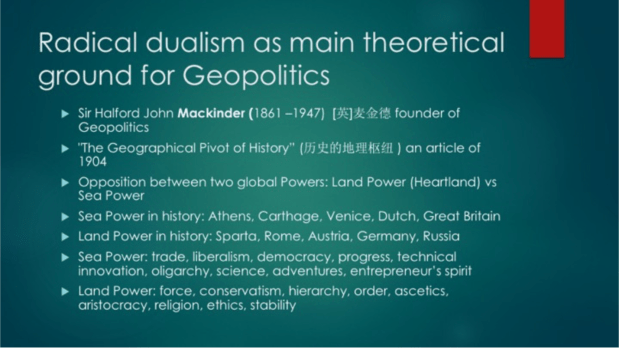

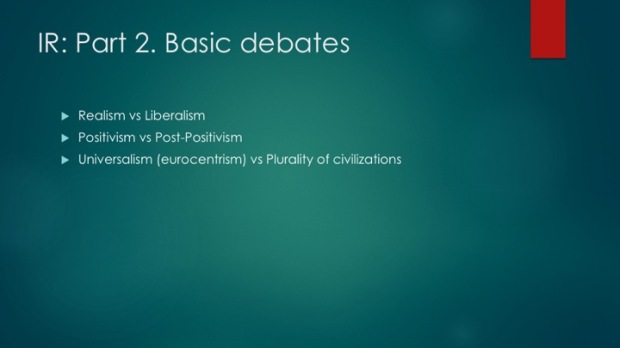

Today’s lecture will be dedicated to Chinese identity in different fields of science. In the first lecture I explained the main structure of the science of international relations, the main concepts, theories, schools, and debates. In the second lecture I explained what geopolitics is. We have explored the geopolitical vision of Sea Power vs. Land Power. In the third lecture I explained multipolarity and multipolar theory, which insists that there should be more than 4 poles, or at least 4 poles – the US, China, Russia, and Europe – and not only one, Western pole. Today, I will try to put China in all of these fields of research in order to better understand what modern China is in these three contexts.

We are going to study the main, most important, or I would say central question: What is China? But we cannot start from the parts in order to come to the whole, because we cannot understand the meaning of the parts without knowledge of the whole. We cannot proceed in the opposite way either, because we do not know the whole. We need to use the philosophical method of hermeneutics in order to discover what China is through the process. We do not know what China is – nobody knows. China is a mystery. We are not going to reveal or explain this mystery, but we are going to enter this mystery, to try and think about Chinese identity, and put China’s identity into different philosophical, geopolitical, and intellectual contexts, to find China’s place in the world, but at the same time to define what China is here. The world is presumed to be whole, while China is only a part, but without knowing what China is or what the world is, we cannot find find the place. We are going to proceed together in this hermeneutic approach from Schleiermacher.

We should establish some hypothesis on what China is, after which we can make a kind of reality-check. This is not a dogmatic definition of China, but a kind of presumption or phenomenological approach. In order to understand this, we need to make some very important statements. Every statement here is of crucial importance.

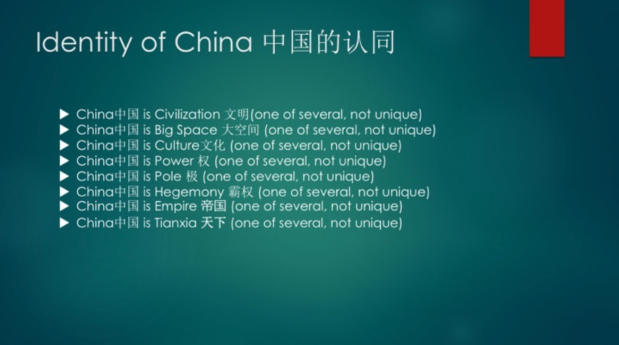

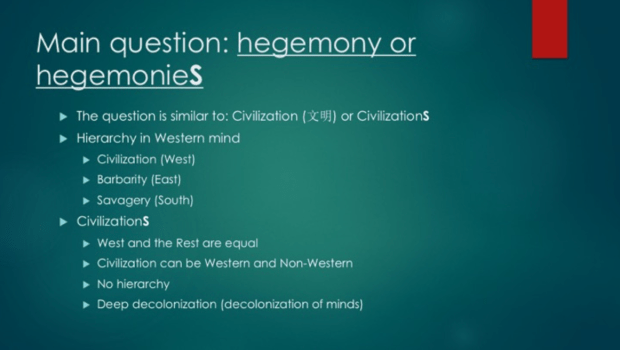

China is a civilization. That means not whole Civilization, obviously, as there are civilizations outside of China. China is one of the many civilizations. Being a civilization, China represents something complete and perfect, autonomous, and self-sufficient. To be a civilization means to have one’s own measure inside, not outside. A civilization can measure its control and define its own values, progress or failure, using its own tools. Civilization means many things. It is the highest point of more complex, integral concepts. It is something that Professor Zhao Tingyang, whom I met in Beijing and I have a great impression of, means by Tianxia (天下). Tianxia (天下) is not a country, it is a system or civilization.

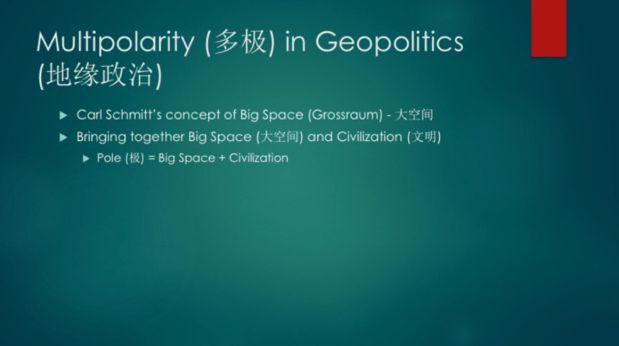

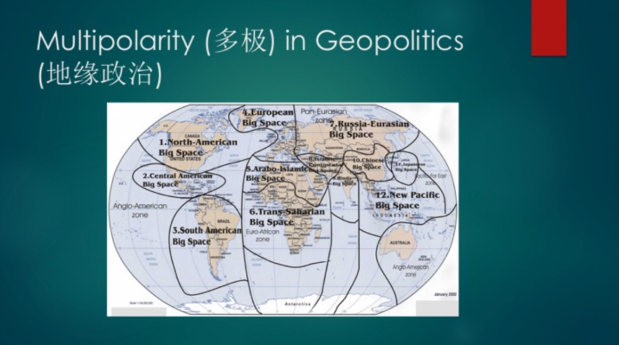

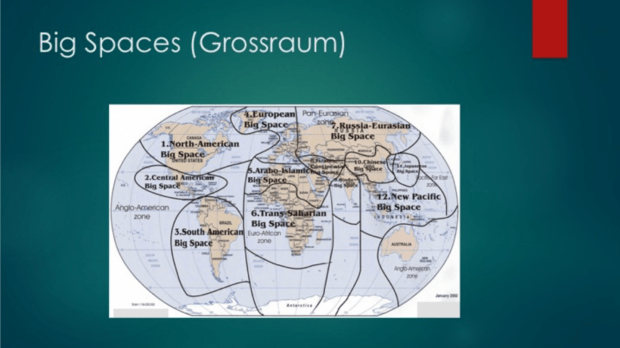

In geopolitics, China is a Big Space. For example Canada, which is a big country, is not a big space, because it could not represent this space as unified, centralized, historically united. North America is a big space, not Canada. Not every geographical big space is a geopolitical big space, but China is. China historically controls a big geographical zone that is united politically, socially, culturally, historically, religiously, by writing, by Han identity, and so on.

China is a culture. Chinese culture is more than the Chinese state, because the people of Taiwan and some non-Chinese, non-Han people share more or less the same culture, such as the Vietnamese, the Koreans, and partly the Japanese. Their identities and cultures were formed under the huge impact and influence of Chinese culture. Chinese culture is something supra-Chinese, something more than Chinese, because this culture can be given to others, and they can share this culture, such as the writing system for example.

China is a power, because it has political, economic, demographic, geopolitical, strategic, and military resources. It can oblige others to do something. If someone wanted to attack China, China could respond in any way. China is a power that can defend its sovereignty.

China is a pole in the multipolar system. I will explain later what concretely this means. When we are speaking about multipolarity, we immediately imagine the Western pole without any doubt as to it being a civilization, power, and big space. But next to the West today, China is also immediately a most important pole in the world.

China is hegemony, but obviously China is not the only hegemony, or leading force. There are other hegemonies outside of China. China is a regional hegemony. It could lead and exercise leadership in some circle around China beyond its borders, but not too far. In some definite space, the same with culture, civilization, and power, China is a kind of center of hegemony that, compared to other countries that are close to China, is a real leading force.

China is an empire, not only in the traditional sense, but also in the idea of unifying national, political units. An empire is not one political state, but something more – a system. Tianxia (天下)can be mentioned here. It is something that unites more than one political subject and can expand its influence over greater space.

Thus, finally, China is Tianxia (天下).

All of these definitions should not be considered in an absolute sense, as all these definitions can be applied to China only if we add “one of several, not unique.” It is one civilization, but there are others. It is one big space, but there are others. It is a culture, but there are other cultures. China is a power, but there are other powers. China is a pole, but there are certainly other poles. China is hegemony, but there are other hegemonies. China is an empire, but there are other empires. That is precisely what we argued with Zhao Tingyang concerning the meaning of Tianxia (天下). I will explain later, but the idea in my opinion, the point of divergence with Zhao Tingyang is that China is one possible Tianxia (天下), not the only one, as there are other global structures. For example, there is the American concept of a global world; there can be imagined the multipolar concept of a global world, and there is one Chinese investment in globalization in the form of a universal organization based on the Tianxia theory (天下 体系). We need to understand this project as one of several. Zhao Tingyang, who is the founder and author of Tianxia theory (天下 体系), has said that his concept has been hijacked by some American professor who has written a book on the American Tianxia. According to this professor, only the American Tianxia is the real Tianxia and China’s is only a provincial version. This means that you can propose your global system, but you cannot be sure that it will be accepted by everybody else, at least theoretically. There is a fight for Tianxia (天下). This is already important because American scholars are beginning to borrow Chinese concepts – that is a very great and positive sign, a real sign of multipolarity.

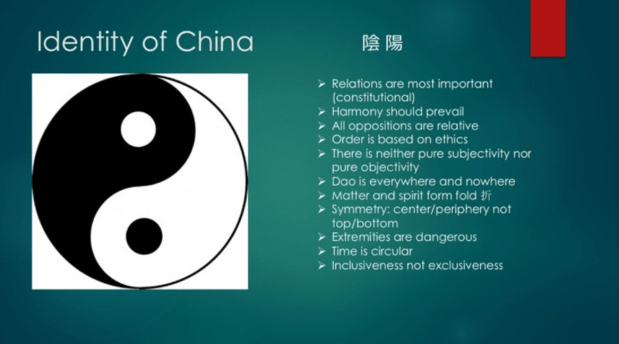

The identity of traditional China can be summed up with other definitions. We are speaking about cultural identity. The Yin-Yang system (陰陽) is based on some important sentences, axes, or laws. Relations are more important than ontological units. It is not of importance what is one thing and what is another, but how they relate to each other – relations and the relativity between two things, rather than these things themselves, because there is no eternal essence. It is not essentialism. Things are changing and relations between them are changing as well. But relations are more stable than things themselves. That is a completely non-Western vision. The Western vision is that things or essences are much more important than relations. Relations could change, but things not. China is quite the opposite. Nature can be flexible, but relations stay. That is the Yin-Yang (陰陽) concept of relations. That is the Yin-Yang (陰陽) vision. Relations are eternal. Harmony should prevail. Harmony is balance, not the victory of Yin over Yang or Yang over Yin. There is no radical opposition between them. There is a kind of play. All oppositions are relative.

Order is based on ethics more than power. Ethics is the highest of things; it is balance and the recognition of the rules of the “play.” Ethics are not a result of the balance of power, as in the Western attitude. There is neither pure subjectivity nor pure objectivity. This is an application of the concept that relations prevail. There is no Western Cartesian subject, nor Western object. There is something subjective in nature, in human culture. You cannot trace here such a radical dividing line as in Western culture. That is why you, Chinese, have such a great admiration for stones. Stones are made by nature. You see the subjective element in stones, for example in Confucius’ temple here in Shanghai which I’ve visited here with Dr. Wang Pei. These stones are considered to be works of art, because nature is the artist, and man is a little bit of nature.

The Dao (道) is everywhere and nowhere. You cannot say that there is a God, Beauty, or a most important value. When you show your ideal, you lose it. When you speak the word, you lose the word. This is a kind of appreciation of silence. As Dr. Pei Wang has reminded, if you listen to silence properly, you can hear the sound of thunder. If you say that the Dao (道) is everywhere or just nowhere, that is a lie. The Dao (道) is outside, as the highest value that encompasses and surrounds everything and is at the center of the thing. It is relational.

Matter and spirit form a kind of “fold.” You can go the way of matter and come into the spirit. There is no strict dividing line between soul and body, because matter and spirit are not in opposition, but are relative. They are something that you cannot define radically as in “here is the body, and there is the soul.” They are intermingled in some way. So there is not only care for the body, because in caring about your body, you are caring about your soul, and vice versa. That is the Tai Chi (太极拳) principle. This is the Chinese way of understanding things.

The prevailing symmetry in Chinese identity is the Center vs. Periphery, not Top vs. Bottom. At the center is the Yellow Emperor Huangdi (黃帝) and there is the periphery. But there is no radical opposition between Top vs. Bottom. Rather it is a matter of concentration and degrees of ontological concentration.

Extremities are dangerous. When you come to the extreme, you lose relations with the whole. Going to extremes, you can lose relations with Being, the Dao (道), harmony, and the game of proportions.

Time is circular; it is not linear. The year starts again exactly at the same point where you begin, the New Year.

There is inclusiveness, not exclusiveness.

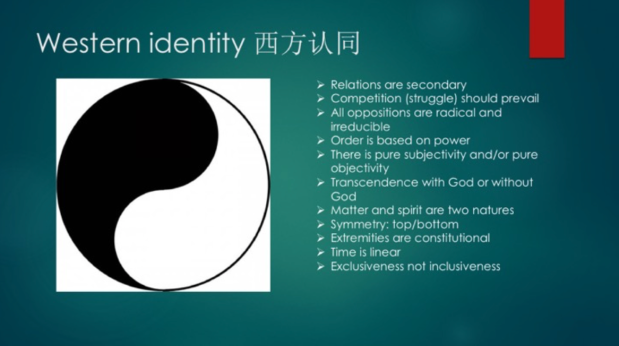

These are the main characteristics of Chinese identity. When we go to Western identity, we lose something important, these two points: the Yin and Yang.

We are coming to a radical dualism that is completely different from Chinese identity. If we try to describe the Western, not Chinese, we will see almost immediately totally different sentences: relations are secondary, and essences are of more importance; competition and struggle, not harmony, should prevail; all oppositions are radical and irreducible. There cannot be an intermediary term between, for example, Good and Evil. There is a dividing line in all the structure of this non-Chinese identity. Order is based on power, not on ethics. Power comes first, while ethics is of secondary importance. There is pure subjectivity and/or pure objectivity – all systems of Western thought are based either on subjective idealism, which in its radical form denies the reality of the external world, or objective materialism, in which case the subject is regarded only as a reflection or mirror of matter. The subject and object are always outside of Chinese culture and philosophy.

Transcendence with God or without God. Transcendence is the absence of something common between the creator and creation. That is a basic aspect of monotheistic religion: God is transcendent, which means that he is incompatible with reality. Only God is; reality is not. In the materialist version, there is the same, only reality is; God does not exist. That is the modern version of the same transcendental attitude. In the modern sense, only material reality exists. As Nietzsche has said, God is dead – we have killed. him So transcendence at the same time prevails in the normal monotheistic theology of Western religions, or without them.

Matter and spirit are two natures. That is an absolute principle of Western identity.

In terms of symmetry, there is the top and the bottom, hierarchies, and taxonomies of different kinds, in which everything is included only based around the vertical line. The top is everything; the bottom is nothing. The top is Paradise or Heaven; the bottom is Hell.

Extremities are constitutional and very important in Western identity, because they create the space, because they go first.

Time is linear. Time is an arrow. Time is not seasons, but is an event that can never, or very rarely, be repeated. The difference between the event and the season is that an event does not repeat.

Exclusiveness, not inclusiveness, means that you organize reality by making strong differentiations between elements. The only way to understand something is to analyze it. What is analyzing in Greek? It is division, separation. To understand a thing, you should kill it and separate it apart, and afterwards try to re-combine and revive the dead system.

That is duality. Chinese culture is non-duality. This is important, because this means that Chinese identity is clearly not Western, but is also not sub-Western or would-be-Western. It is a completely different world organized on a different basis.

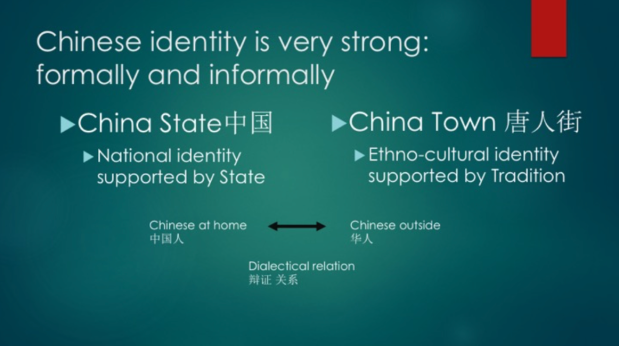

Now we see how deep Chinese identity is. When we speak about the China State, 中国(Zhōngguó), we can say that there is a national identity supported by the Chinese state. This means that the things I have mentioned exist only because of the state, the Confucianist state, the Imperial state, the Communist state – through all of Chinese history, there was a state that promoted these values, the values of Chinese culture, with an educational system, traditions, and way of life – everything was based on these continuations of Chinese identity. But when we go to China Town (唐人街) in the West, there is no China State. There is no necessity to follow this route by going abroad, and one can easily accept the values of other cultures. Sometimes there are no obstacles. But in Washington, in modern days – I was there in 2005 – near the White House, there is a huge Chinatown where everyone is Chinese – with Chinese restaurants, Chinese names, Chinese food, and Chinese speaking Chinese. They are not obliged; there is no state obliging them to be Chinese, but they prefer to stay Chinese. So here we have something more than an artificially constructed identity. We have something deeper than that. If we say that by changing the Chinese state, you will receive another culture, then Chinatown is a great example that this is not so simple. Sometimes Chinese live abroad 10, 20, sometimes 30 years, return to China and they are totally devoted to the Communist Party, to Chinese identity and Confucianism.

That is the great resistance of identity. Identity is not only about the state, nationality, and education; it is much deeper. Chinese identity can be preserved, developed, affirmed, and conserved in different situations and societies. Between the Chinese in China and the Chinese abroad, there is an important dialectical relationship. Chinese identity could exist outside of the state, and if you were to ask Chinese outside what kind of order they prefer, they will almost totally prefer the Chinese order and way of life. That is existential. “Chinese” is defined by Chinese culture, not by the outside, external structure of the state or society. The meaning of Chinese identity is such that it is already included in it. Outside, things can change, while inside there can be a balance – this is the relations-state. For example, you could modernize some part of your society, but other parts will be more conservative, in order to preserve the balance. That is flexible, not radical; this is an inclusive, relations-based, and very stable Chinese identity. It is eternal, like the seasons, or the Mandate of Heaven – you could lose such with one emperor or system, but you will certainly find it with another. You can return to the same point and start the next cycle, the next year.

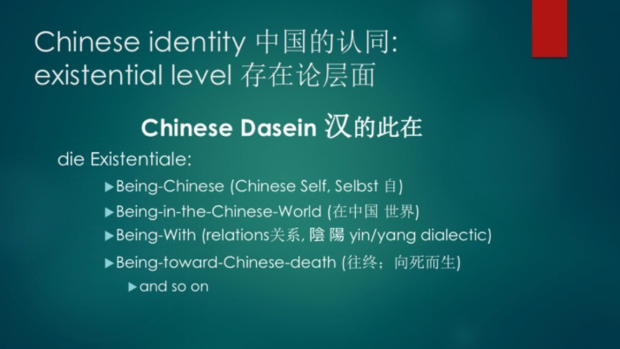

What we get from this analysis, this comparison of the China State and Chinatown, is that Chinese identity is deeper than both. The China state, and the Chinese living outside of China, have a main, common denominator. I call this the Chinese Dasein (汉的此在). Dasein (此在) is Heidegger’s term. I do not think we should use here the concept of Zhōngguó (中国) because it is too political, national, or related to the State. We should use here Han (汉), that is precisely the core of the Chinese Dasein (汉的此在). You can transform into Han nomads from the North or the population of the South of China, but Han is the core of Chinese identity. Han-Being is existential and ontological.

We can describe the Chinese Dasein (此在) using Heidegger’s methods in terms of Being-Chinese. You cannot be without being Chinese first. Being Chinese, you understand what Being means for Chinese, but without that you have no access to this existential understanding. Being-in-the-World, Im-der-Welt-Sein, is translated here as Being-in-the-Chinese-World. The Chinese world does not mean Zhōngguó (中国), the Chinese State, but is the world you interpret, see, and create over the course of this interpretation. You can live in a Chinese world while living inside or outside of China. Being-With, Mit-Sein in German, another concept of Heidegger’s, is the core of Chinese identity, as you cannot be alone, but always surrounded by other Chinese. You are with your family, ancestors, with the Other, the Chinese writing system, your thoughts. That is the Chinese dialogue. You are always with. With what? With something Chinese.

Being-Toward-Chinese-Death is the most radical definition of Being-Here, or Dasein (此在). I once told the last living disciple of Heidegger, Professor Friedrich von Hermann in Freiburg, that I believe in a multiplicity of Daseins – there is not only one universal Dasein for everybody, because there are different cultures and their own different descriptions of Being-Here. He said that Heidegger would not approve of that, because Heidegger believed in the universality of Dasein (此在), and the argument for such is the universality of Death. I responded: Not at all! In different cultures, there are different deaths. For atheists, death is the end of everything. For Christians, the way of death is based on the soul and post-mortem journey into Heaven and Paradise. These are completely different experiences. I think that there is or should be a Chinese understanding of Death inscribed in the Chinese culture of the return of the ancestors. The family, the house, the tradition are more important than Death. Entering into Death or coming to the world, there is this circular rotation. It is not a kind of interruption of continuity. There is continuity in Death. There could be a Chinese Death, a very special one. Being Russian, I could speak more about the Russian meaning and way of Death, but I leave it to you to explore this existential of Chinese Dasein (此在) more.

As for the Chinese Logos, this is is a more evident part of Chinese identity because it is explicit. If existential identity is implicit, or hidden on the existential, basic level of presence in the world, then the Logos is quite clear. In traditional society, we have the Chinese Logos with Confucius, Laozi, and Chinese Buddhism – these are the three great systems of Chinese culture and traditional society. Tianxia (天下) is precisely a traditional concept, not imagined byProfessor Zhao Tingyang. In the Zhuangzi text there is a chapter called “Tianxia.” It is the 33rd and the last in traditional division of the whole book (Miscellaneous Chapters —雜篇 Zapian).

Ethical order and meritocracy. Professor Daniel Bell has written a very interesting book on the Chinese model of meritocracy, which I recommend – “The China Model: Political Meritocracy and the Limits of Democracy”.[1]

And so, there are very explicitly developed systems of how to understand the basic identity on the level of Logos. All the definitions we used in the beginning can be found here, very rich, with details, in books, systems, and schools. This is a huge cultural and intellectual heritage based on Chinese identity.

In modern society you have another form of the Chinese Logos: Mao Zedong, socialism, and Chinese modernity are a kind of new form of the Chinese Logos adapted to new challenges in your history. In your present situation, this is just as important as the heritage of traditional Chinese identity. These are new names for things. Confucius said that we need to improve the names of things. Mao Zedong has improved some names to adapt them to reality without destroying relations between things, while continuing the same Chinese identity. In this situation, Deng Xiaoping added to this vision some new features, such as opening to the West – but not in order to give up your identity, but with the flexibility to empower your identity, to stay Chinese in the new global world.

In modern society you have another form of the Chinese Logos: Mao Zedong, socialism, and Chinese modernity are a kind of new form of the Chinese Logos adapted to new challenges in your history. In your present situation, this is just as important as the heritage of traditional Chinese identity. These are new names for things. Confucius said that we need to improve the names of things. Mao Zedong has improved some names to adapt them to reality without destroying relations between things, while continuing the same Chinese identity. In this situation, Deng Xiaoping added to this vision some new features, such as opening to the West – but not in order to give up your identity, but with the flexibility to empower your identity, to stay Chinese in the new global world.

It is not globalization that is using China. It is China that is trying to use globalization. This is very interesting, but very dangerous, because in coming into a world that is not Chinese and is organized on a completely different set of concepts and values, it is easy to lose identity. Maybe not for you, as we have discovered that your identity is so strong that you can accept this challenge. This is the difference between Chinese and Russian history. Russian identity is not so strong. Coming to meet the West, we have failed, we lost our country, and almost lost our soul. In the last moment, Putin appeared. Our situation was extremely critical in the 1990’s, and entering into globalization, we accepted it too deeply, we let it enter too deep into our system and it almost destroyed our society.

Now we are coming to future Chinese society, what I call the Great Synthesis of the traditional and modern society. That is precisely what Comrade Xi Jinping declares. He declares the Chinese Dream. China’s Dream is not only an imitation of the American dream, with consumption and comfort, but is a dream to re-affirm your eternal identity in new conditions, to join traditional society with its values and modern society. It is precisely Confucianism and Maoism – the traditions of ancient China and modern China. That is a kind of Chinese post-modernity or Chinese future. That is the Logos based on Chinese Dasein (此在).

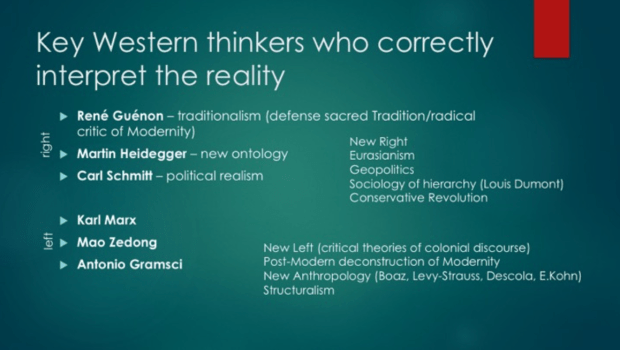

In order to reinforce and empower this Logos for future Chinese identity, you could use some European authors who are very critical of the European Logos and European Modernity, which are very useful to promoting your understanding of the West.

René Guénon, the founder of Traditionalism, and his defense of sacred tradition and radical critique of modernity are important to defending your traditional values, such as Daoism, Buddhism, and all the traditions of your society. It is a defense of Traditional society.

You can use Martin Heidegger’s new or fundamental ontology, which is already being done in Chinese society as I have remarked with great pleasure, and I am happy that Heidegger is very well known here. That is something incredibly rich and important.

Carl Schmitt’s political realism helps with reading many different aspects of Western political thought.

I would also recommend the ideas of the New Right, Eurasianism, Geopolitics, the sociology of hierarchy (first of all the French sociologist Louis Dumont), and the concept of Conservative Revolution.

The Great Synthesis should include revolutionary and traditional elements. These are all considered more or less on the Right, but as for the Left, I think that anti-capitalism and the anti-capitalist ethics of Karl Marx are extremely important, maybe not the technical aspects of his thought which is a little outdated. Anti-imperialism is an important concept as well. Mao Zedong, as the founder of Chinese socialism, included the peasantry and traditional society in the revolutionary class, whereas in Russia Lenin excluded the peasants from the revolutionary class. That was the reason for the near genocide of the Russian people. You were much more clever.

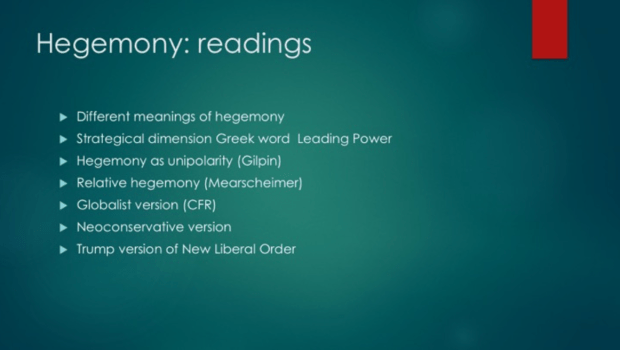

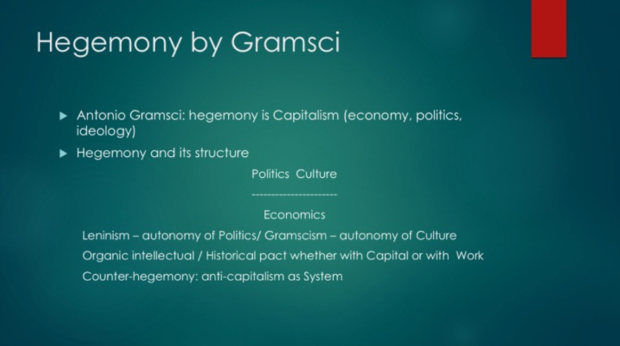

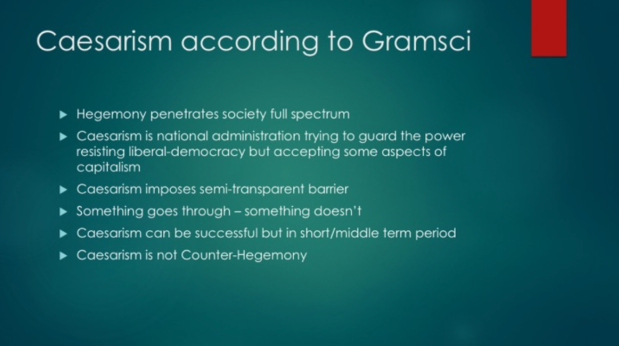

And I suggest Antonio Gramsci, many of whose ideas, such as Caesarism, are very important now and applicable to the present situation. The historical pact of intellectuals and Gramsci’s concept of hegemony, are of use as well.

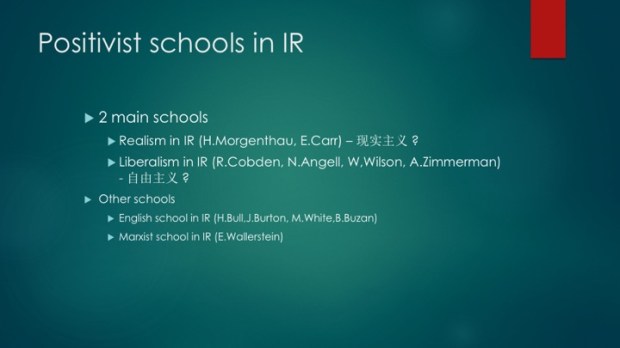

The next step is China in International Relations.

The next step is China in International Relations.

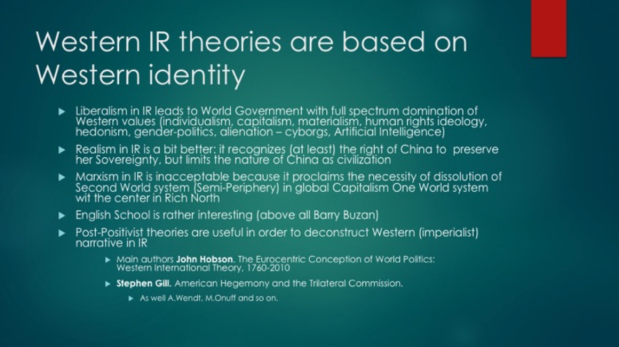

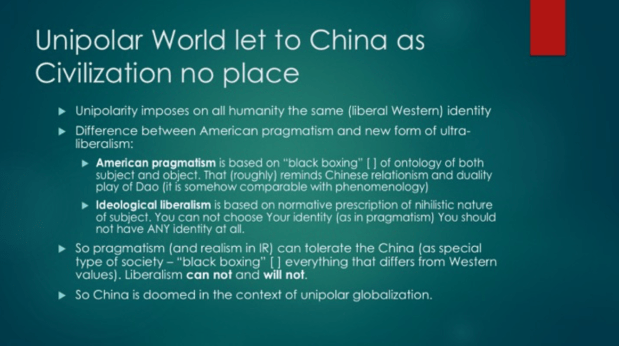

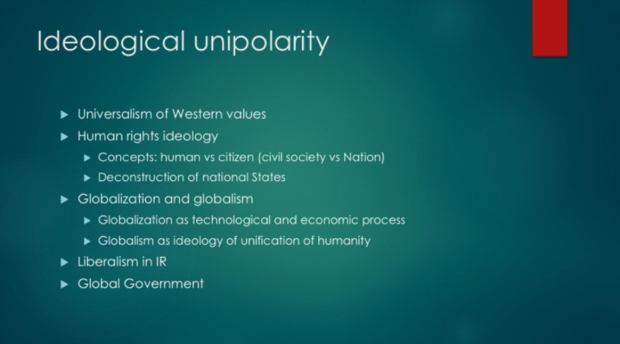

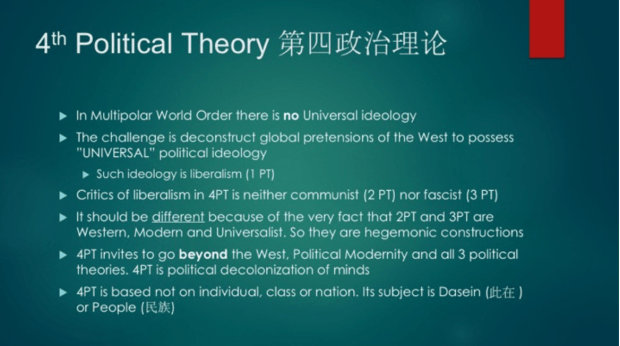

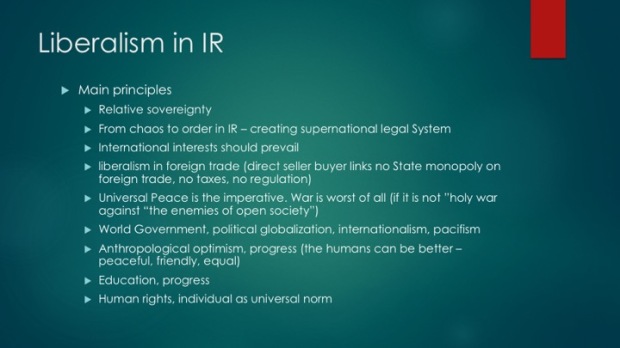

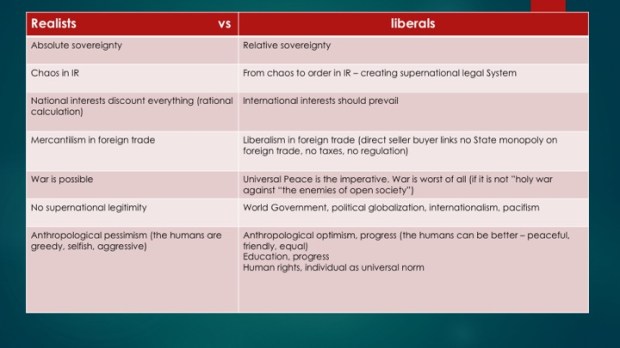

Liberalism in IR is based on the full spectrum-domination of Western values. We should not mistake this situation. All the classical theories of Liberalism in IR are based on the idea that Liberal Western values should prevail on the global level. You have no chance to have Chinese identity or Chinese sovereignty within this concept, because Liberalism in IR explicitly thinks that there should be the dissolution of the nation-states, the dissolution of all forms of collective identities in favor of only one type of identity – the individual – and that there should be an international structure or institution over states whose authority should be recognized as law.

That would mean the end of China not only as a state, but also Chinatown – the end of Chinese identity as a community. Sooner or later, the liberals will remark that the Chinese prefer their cultural identity, and they will attack that, try to destroy it. This is not religious because all the religions of the West are more or less destroyed already by Liberalism in the West. When the Liberals remark that there is something not so much Western and individualistic with Chinese identity, then they will begin to attack not only the state, but also Chinese culture.

Liberalism in IR excludes China. It is unadaptable. It is a projection of Western hegemony, the Western system of values, and unipolar model which, in the eyes of Liberals, should be imposed on a global scale.

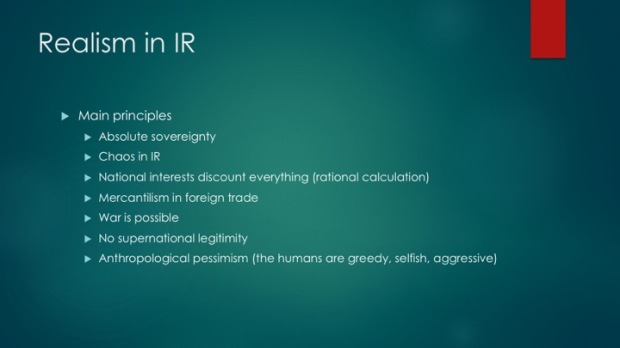

Realism in IR is Western-centric and modern, but at least it recognizes the right of China to preserve her sovereignty. Realism does not enter into the details of civilization. Civilization does not matter to realists. But realists think that if there is a power that can defend itself, then we should take it into consideration. That is a little better than Liberalism. They will compete with you, maybe fight, maybe conclude an alliance or peace, but a priori this is not planned destruction [of China] as in Liberalism.

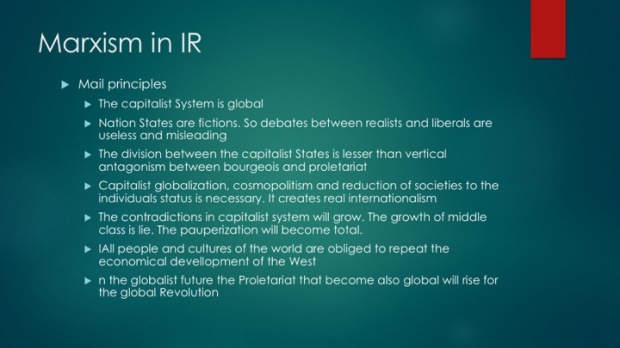

Marxism in IR is completely different from what you might think. It is not the idea of Soviet or Chinese international politics. Marxism in IR is based on the idea that all nation-states should be dissolved and global capitalism should prevail; there should be the destruction of all societies, and the transformation of humanity into two classes with no nation, identity, state, or type of civilization. This is cosmopolitanism. The global population is made into a mixture of cultures, peoples, ethnic groups to create a post-national, post-ethnic, post-national confusion of all races and ethnic groups, in order to divide them into two classes: the global proletariat and global bourgeoisie. That is applied to IR by authors such as Wallerstein.

In Wallerstein’s global system, there should be the transformation of the global world with one center of developed countries and the periphery of underdeveloped countries. In between them, China, Russia, India, Brazil, and the semi-periphery, should be destroyed, but the oligarchic, capitalist part of these semi-periphery countries should be integrated into the global elite, and the others should become more and more poor. Immigration is an ideological concept to promote this, a tool, to accelerate this process. Through mass migration, they will transform the world into a culturally homogenous structure with the only dividing line being between poor and rich – and after this will start the global proletarian revolution. Thus, in the short term, Marxists in IR serve the Liberals because they say that first capitalism should prevail. They regard Stalinism, Sovietism, Russian socialism, Chinese socialism, and Maoism not as authentic socialist experiments, but as kinds of “National Bolshevism” or “National Marxisms.” They think that you do not have socialism, but a kind of national-bureaucratic, totalitarian state ruled by a political elite that should be destroyed. Marxists in IR are not friends. Beware of these “Marxists” and “Leftists.” They are a Fifth Column of Liberals in IR. China has nothing to do with them.

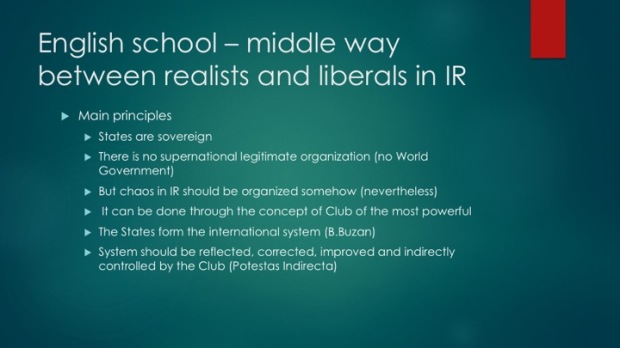

The English school is rather interesting – above all, the IR author Barry Buzan. The English school thinks that there should not be a global government, as the Liberals insist, but a set of rules established by a club. The most powerful countries should accept, as a club, some rules and relations that will be a kind of constitution of the club. A club is not an authority, but a matter of self-respect and social position, not something that you are obliged to follow. You are not obliged to follow the rules of the club, but it is “better” that you accept them to increase your status. The “great countries” of the G20 and G7 are a club. Their decisions are not obligatory, but are important to follow. If someone is thrown out of the club, as we, Russia, were after Crimea, we are supposed to feel “awkward” – not in the face of an authority that can punish us like a criminal, but in the face of a kind of “moral disapproval from the club.” The English school of IR explains this perfectly.

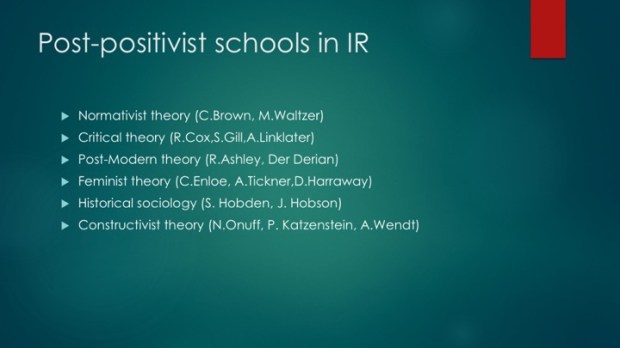

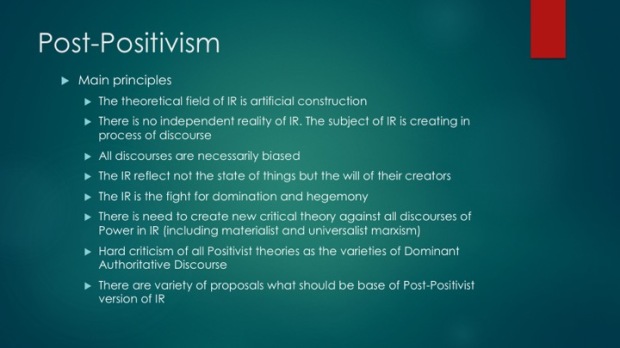

Post-positivst theories are useful in order to deconstruct the Western imperialist narrative in IR. The post-positivists propose almost nothing, but their radical criticisms and deconstruction of discourse with post-modern tools are very useful when we have to defend our identity. It is a tool for defense and offense. If a Chinese specialist in IR can understand what post-positivist IR theories are all about, they will be completely free from any kind of complexes – they could speak with any Western critics of the Chinese system using their own tools. This is a marginal sector of IR that is growing in importance. I recommend above all two authors that should be carefully read and which are very important for Chinese IR in general: that is the Australian scholar now living in Great Britain, John Hobson, and his The Eurocentric Conception of World Politics. He is anti-racist, rather left-wing and a Gramscianist, but his work is perfect, remarkable. He is accepted as a normal scholar, as not too much of a radical, but his work is quite a miracle in its criticism of all kinds of IR theory based on the manifestation of Eurocentric and racist -isms. His offers the best criticism of racism that I have met in the field of IR. The next, maybe more technical author is Stephen Gill and his work, American Hegemony and the Trilateral Commission, which is a Gramscian application of deconstruction to the temptation to create global government on the part of some American internationalist, liberal institutions.

You can use these two books in order to not only defend Chinese identity and politics, but as well to lead the intellectual attack on those who come and say that you have no human rights, no democracy, a totalitarian system, and so on. You can immediately cite a few pages from these two books and they will disappear, because their discourse against yours would be a defense of pure imperialism, racism, and nationalism. This is very important from a theoretical point of view.

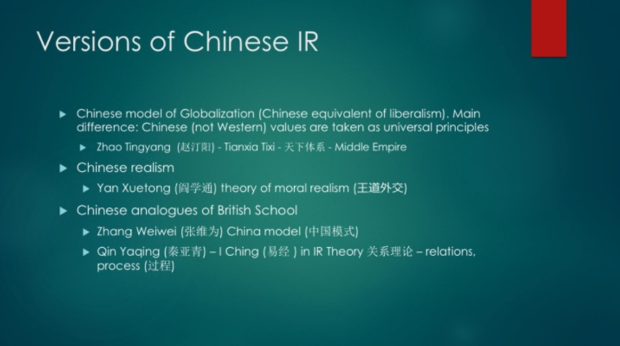

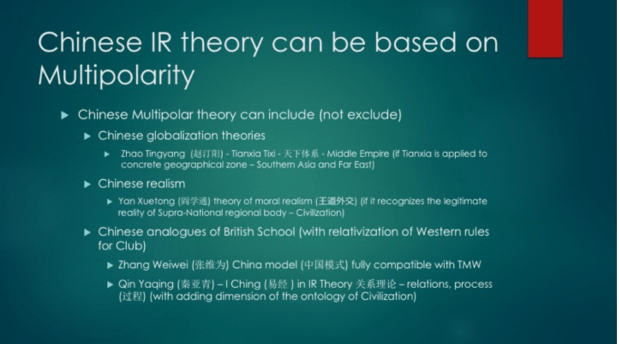

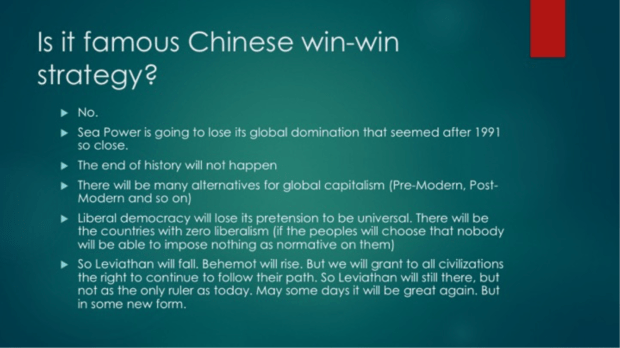

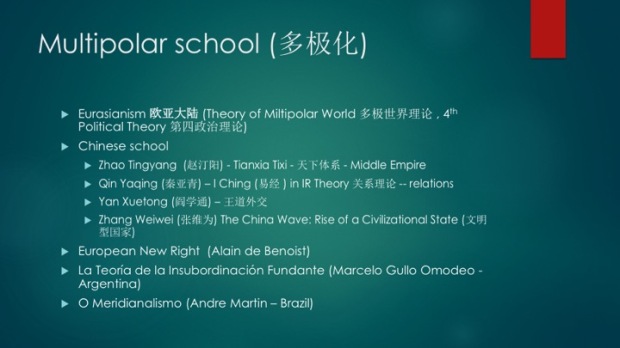

There are some versions of Chinese International Relations theory. I think that there is a Chinese way of globalization. Professor Zhao Tingyang thinks that the global world and global governance should be organized based on the Tianxia principle. I don’t believe in that, but it is a very good idea if you insist on your own globalism: “Let’s hear what we, Chinese – strong, powerful, rich, a rising power – have to say with our own version of globalization.” That is a very smart move and very interesting concept, but I hardly can imagine that the globalists who have a completely different understanding of what globalization is, could seriously speak about that.

The Chinese realism of Yan Xuetong as a concept is not pure realism. Yan Xuetong proposes that a realistic understanding of the balance of power, alliances, should include an ethical dimension, something completely unknown to realism. This is a kind of “moral realism” (王道外交) or “ethical realism”. That is Chinese vision of realism in which there is not only the relation of powers, badao, but also an ethical dimension, wangdao.

As for the Chinese analysis of the British school, I could say that the China Model of Professor Zhang Weiwei is kind of that. “Let us have some rules for international behavior, some club, but do not impose on us your rule in an authoritarian way. We can hear you, we are open to debate and dialogue”, and Professor Zhang Weiwei represents this brilliantly with his travels through the West. He perfectly well explains Chinese identity without letting others convince him or insisting too much on the Chinese truth. This English club-school way of promoting Chinese identity is very inclusive, mild, harmonious, polite, and Confucian.

One interesting idea of Qin Yaqing insists on the Guanxi concept that relations are more important than essences. We need first of all to concentrate on relations between countries and try to moderate relations and meta-relations without going into the essence of “good”, “bad”, “real power”, “pretending power”, etc. On the basis of relations, we can construct some specific balance for the system of IR.

So, while there is not yet a Chinese IR theory, but there are some fruitful approaches.

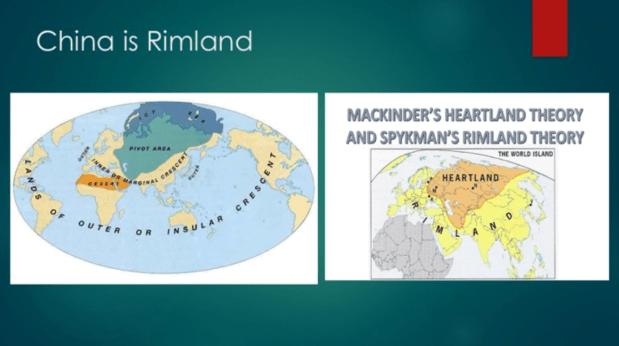

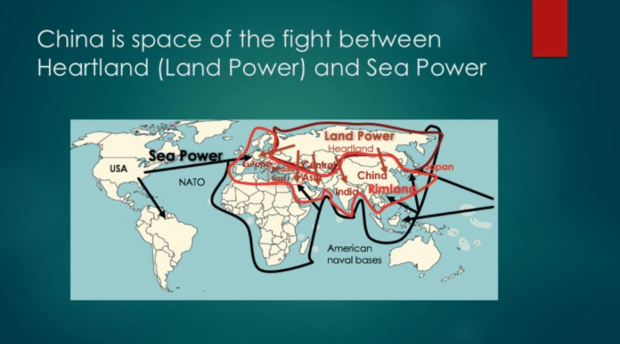

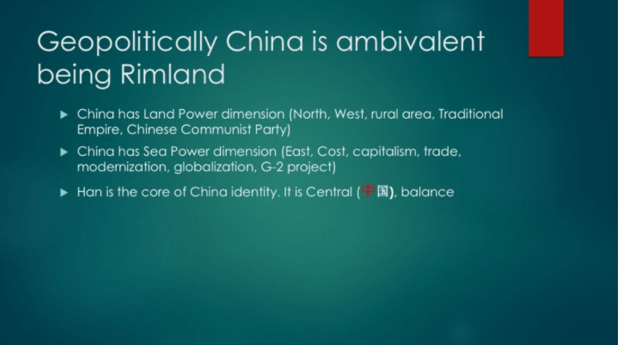

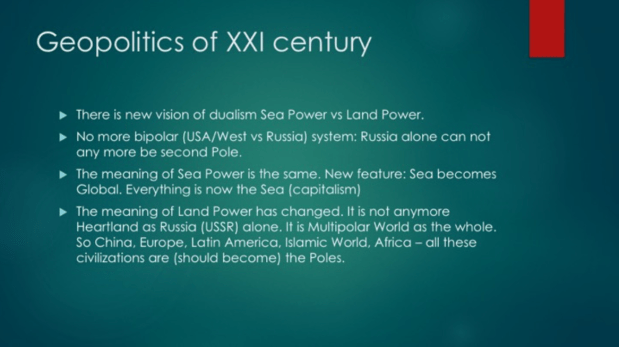

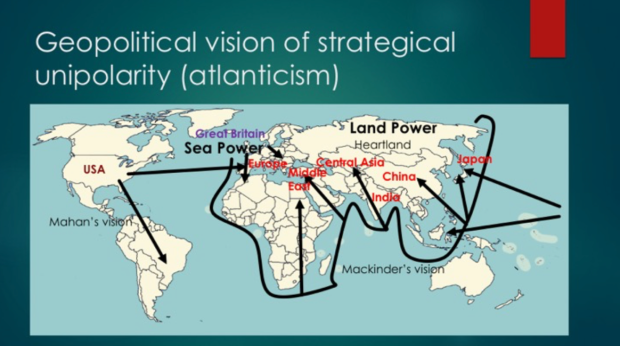

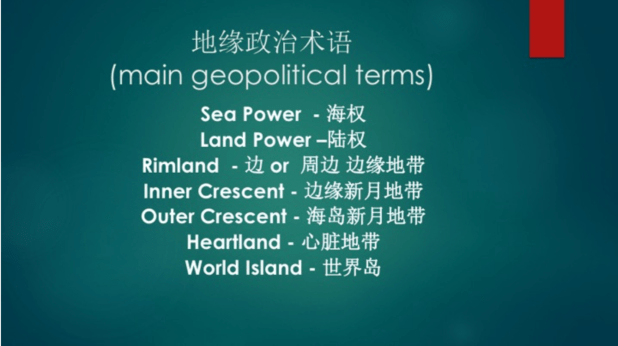

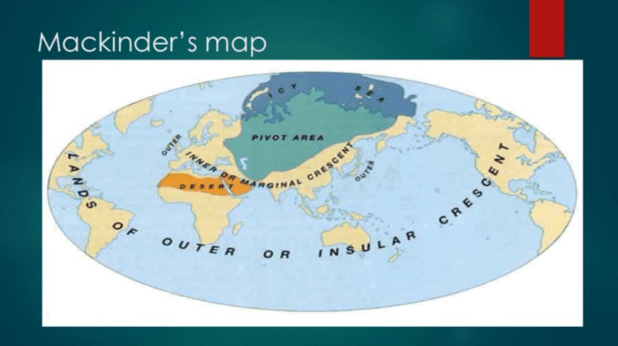

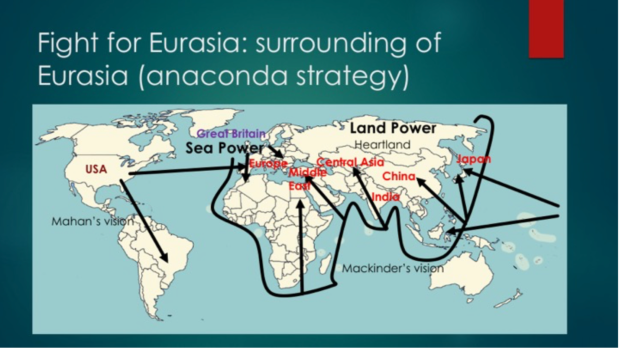

Now for China and geopolitics. In classical geopolitics, on Mackinder and Spykman’s maps, it is absolutely clear that China represents Rimland, the coastal area of Eurasia. All zones of Rimland are divided between the pivot area, Heartland, and Sea Power. But at the same time, Rimland, and such a huge part of Rimland as China, could have its own Heartland, its own continental core, next to its coastal component. China is its own world that could apply geopolitical principles to China herself. It is too great to be only a part of Rimland. It could also be an independent part of Heartland, having its own Rimland or coastal area. In traditional geopolitics, Heartland and Land Power are Tradition, and Sea Power is modernization. The same is in the case of China: China’s coastal area is much more modernized and involved in capitalism, while the inner part is more traditional.

China, as Rimland, is a zone in the balance of global power between two civilizational powers, Land Power and Sea Power, fighting together for control [over Rimland] from Europe through the Middle East and Central Asia to China. All of this region is a kind of zone for world rule.

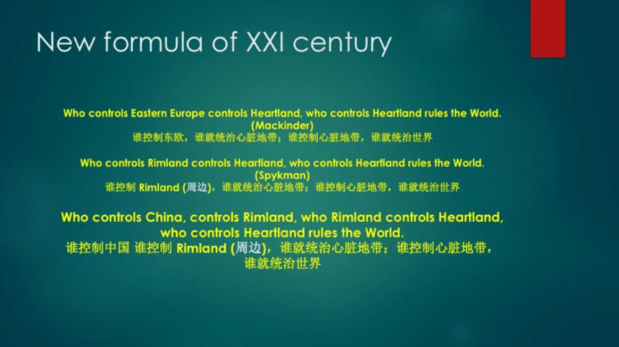

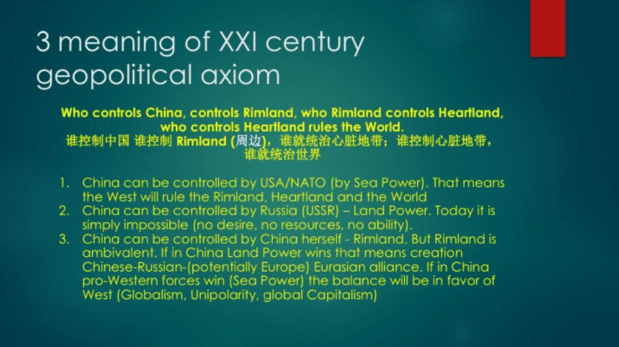

There are two classical formula:

“Who controls Eastern Europe, controls Heartland; who controls Heartland, rules the World.” (Mackinder). This version of Mackinder’s was from the beginning of the 20th century.

In the middle of the 20th century, when the importance of other places of Rimland came to be understood in the process of de-colonization, another geopolitician and follower of Mackinder, Spykman, transformed this geopolitical formula:

“Who controls Rimland, controls Heartland; who controls Heartland, rules the World.” (Spykman)

If Eastern Europe was the most important space to contend Heartland and Russia, according to Anglo-Saxon global politics, then Rimland is in a much broader sense, but with the same logic of the opposition between Sea Power and Land Power.

Now there is a formula for the 21st century, when China is the greatest power of Rimland:

“Who controls China, controls Rimland; who controls Rimland, controls Heartland; and who controls Heartland, rules the World.”

We have this new definition and formula because now that China is not an object, as Rimland was 60 or 70 years ago, and China is a giant, a rising power, it is no longer going to be controlled by external powers. It is quite out of the question and impossible in the present situation that Russia could pretend to control China, and there is no desire, will, resources, possibility, capacity, or ability to do so. The West, Sea Power, is also more and more understanding that it cannot control China.

Thus, maybe as Graham Allisson says, there is a growing danger of confrontation precisely because the most important part of Rimland today is not controlled by the West. That is a serious challenge to Sea Power. That is Allissons’s interpretation of Thucydides Trap.[2]

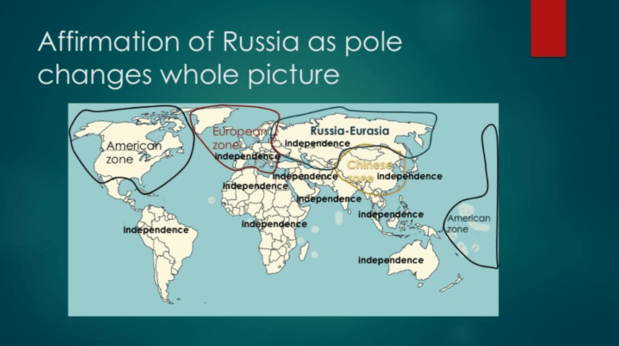

There is only one thing that could change. If China will recognize herself as Heartland, it will rule herself and maybe Rimland, and maybe thereby including the Russian Heartland, the world. But now we cannot imagine that as a result of occupation, expansion, imperialism, and so on. It is only free will, based on China’s free decision. It is very interesting how the balance of geopolitics during the century has changed. I think that the rise of China changes everything.

China has a Land Power dimension (the North, West, rural area, Traditional Empire, and the Chinese Communist Party). China has a Sea Power dimension as well (the East, Coast, capitalism, trade, modernization, globalization, G-2 project). Going in the Sea Power direction, China could be part of the globalist construction. But there is also the core China, the Central China [the Middle Country, Middle Kingdom, Central] dimension of China that is precisely what unites the two sides of China – the Land Power and Sea Power. This is the key to the geopolitical future.

Western hegemony is represented in strategy, civilizational values, technology, liberal democracy, and universal type of social organization, such as cosmopolitanism and individualism and so on. Unipolarity is something that happened after the fall of the Soviet Union. In that moment, Fukuyama wrote his famous text on the End of History because, according to him, there was only one pole, one system, one hegemony, and no one at the time could imagine a challenge to it. That was the unipolar moment based on the clear domination of the West. That was not globalization as a sum of different cultures and peoples coming and living together and sharing values. The Western values – liberal democracy, global capitalism, individualism, cosmopolitanism, and the Western modern and post-modern liberal understanding of man – were taken as universal and imposed on everybody. The last formal power that fought against that, the Soviet union, had fallen. That was the logic of unipolarity.

The unipolar world leaves China as a civilization no place. The unipolar world gives a place to Chinese as individuals, but only as how they understand Chinese should be: they should be individuals striving for comfort, a career, good living, materialist standards, and being part of the global world with the same iPhone, jackets, interests, movies, entertainment, food. Chinese as individuals will be accepted as any other, but Chinese identity will be rejected. The password for the unipolar world is “I am an individual, let me in.” You cannot join the unipolar world as Chinese individuals with all the baggage of your Dasein (此在), your existential ground, your Logos, your Communist Party, and Confucius.

This is the special exclusiveness of liberalism. The main book of modern Liberalism and Neo-Liberalism, is Karl Popper’s The Open Society and its Enemies. There is class war in Marxism. There is race war in National Socialism. And there is the war between the Open Society and its Enemies in Liberalism. This is absolutely racist. If you are considered to be one of these enemies, you are out, you are excluded, you are called a fascist, communist, Stalinist, Maoist, and so on, the Gulag and Auschwitz and so on, you are just barbarians. You can enter only accepting what they think you should be, not what you are or want to be. They will try to control your desires, your will, your interests, your sympathies, choices, and demands. You should follow their rules, protocols, system, and only after that will you be a “friend of the Open Society.” The Open Society is an exclusive concept.

What is the difference? Fascists regard other fascists positively. Communists can consider other communists friends. If liberals consider all other liberals friends, then this is the same. But fascists started to destroy the other races, considered to be un-human. The communists, in our experience, almost destroyed millions of our population, considering them to be bourgeois or not revolutionary. Liberals destroy the enemies of the liberal Open Society by bombing Libya, destroying Iraq, and so on. Everyone who is against the Open Society should be eliminated, destroyed, killed. That is nothing new, maybe something simply more or less human, but we should clearly understand what unipolarity and Western hegemony mean. They might be friendly, but they are hiding a knife. We should be aware of this in the very least.

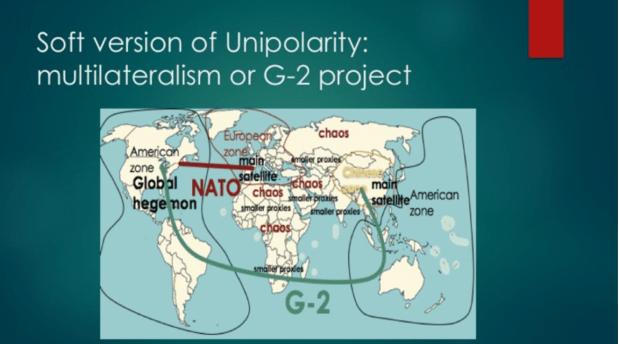

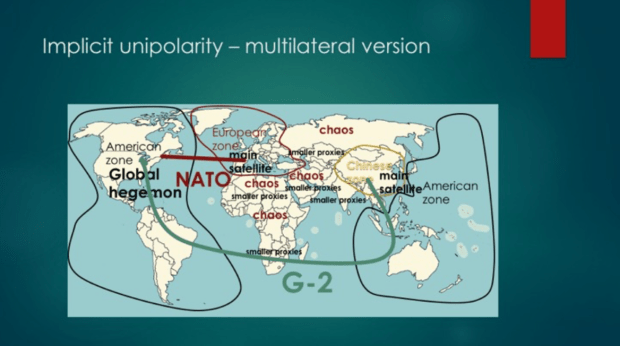

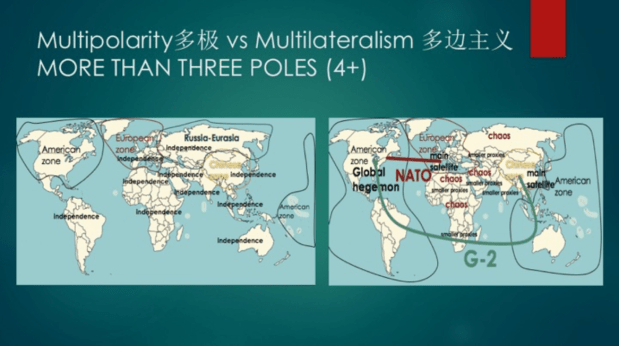

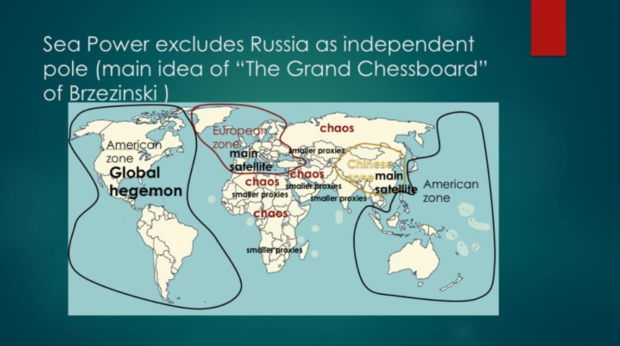

Here we can see a soft version of unipolarity. The West proposes to the other powers, Europe and China, to be friends, as in the G2 or NATO concept. But what goes on in other parts of the world? Bloody chaos, civil wars, radical political and religious extremist forces, killings – as has already happened in North Africa. The same fate is destined for Russia in the writings of Zbigniew Brzezinski, who said that Russia should be Balkanized. When Bush was in Moscow once in the early 2000’s, he said to Putin: “Please wait, you will have the same democracy as in Iraq.” That was precisely when the US was in the process of killing hundreds of thousands of people there. Putin was very shocked because he somehow imagined Russia’s future differently. But that is the idea of what will go on outside of these zones – a kind of manipulated chaos.

There are three ways for China to deal with hegemony.

1. It could accept Western hegemony, which is not so strange, I think. Since Deng Xiaoping’s concept of transformation, there is some kind of threat of Chinese society going to deep into the consumer society, the Western way of life, and capitalism and globalization, towards finally accepting Western hegemony. If we do not care about Chinese identity, maybe accepting Western hegemony is the solution, or at least an option. If every Chinese accepts this global society, with some skills and talents allowed for the Chinese people, maybe there will be some solution, but there will be no Chinese identity. Some people care about Chinese identity and sovereignty; others don’t. I do not think that there are too many of them, but theoretically this could be so, because hegemony is not only the strategic domination of the West, it is also values and standards. So a liberal, pro-Western, pro-Popper, pro-Soros trend could be identified in Chinese society. I presume that there could be some educational structures, professors, and trends in cultures – maybe not dominating, because you have the Communist Party, the main guard of Chinese identity and the present Logos, and tradition. Nevertheless you have taken in a little poison, and poison can be active in some cases.

2. You can affirm and develop Chinese regional hegemony. That is the realist, nationalist trend. You could call this the badao, with wangdao adding an ethical dimension. That will be your Chinese way. But I think that this is the best way for China to consider hegemony. You could say that your hegemony is more or less in some area, maybe in some ways outside of Chinese borders and including other spaces, but you could also make differences – in one situation, political, in another economic, in a third hegemony could be cultural. Hegemony is not bad in itself. But the most important thing is to have a just model for hegemony. For that balance and harmony, Chinese culture has many experiences. Balance is a part of Chinese identity. Chinese hegemony could be based on your own character and identity, not on some universal rules of hegemony.

3. Lastly, you could try to put Chinese hegemony on a world scale, to propose a Chinese globalism. I have heard a kind of fear or idea among serious people in the US, the West, and Russia of the myth of Chinese globalization. Maybe you have no idea or project to impose hegemony on a world scale, but others think that you have such plans. You need to accept them, because if someone thinks that there is something, that means that on the social level there is something, maybe only in their minds, but that is how the world is shaped – by projections of our thoughts. You should not say that you have no such [hegemonic] idea. There are many people in different cultures who are absolutely sure that you have such ideas. You need to take that into consideration. If you know that there are such people, you will speak to them more carefully. You should somehow promote your version taking into consideration how they regard China.

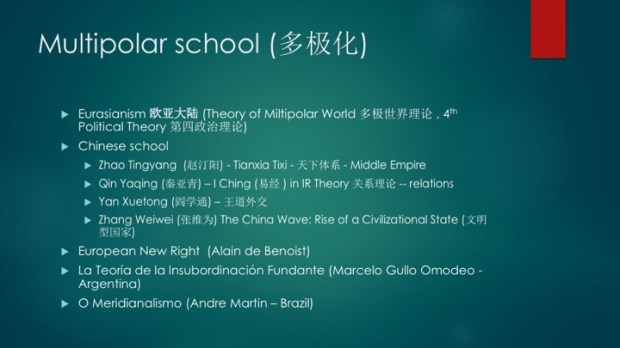

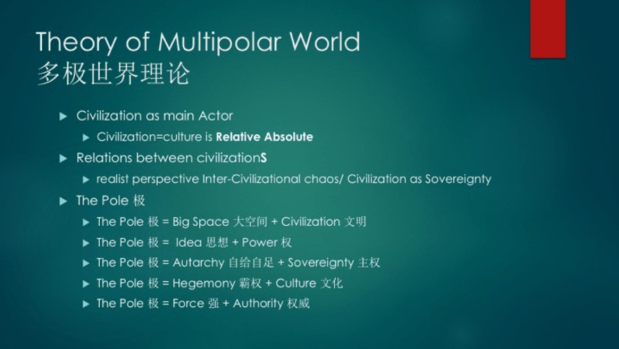

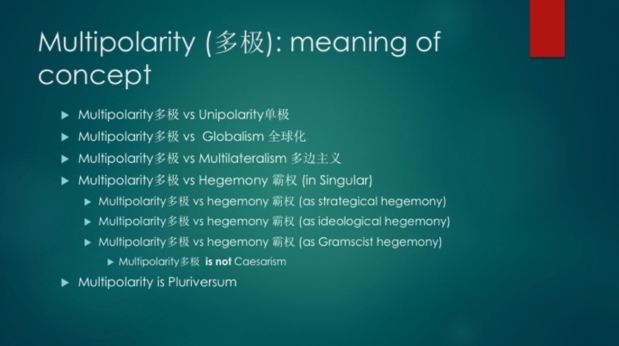

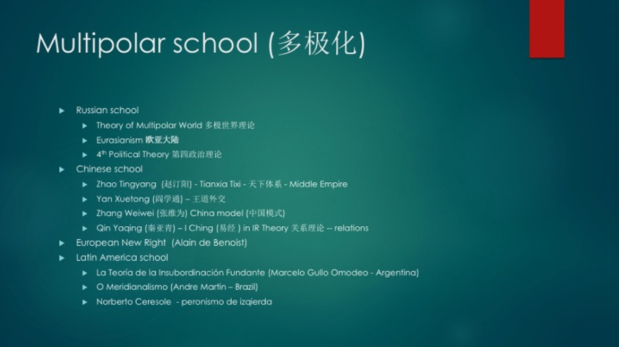

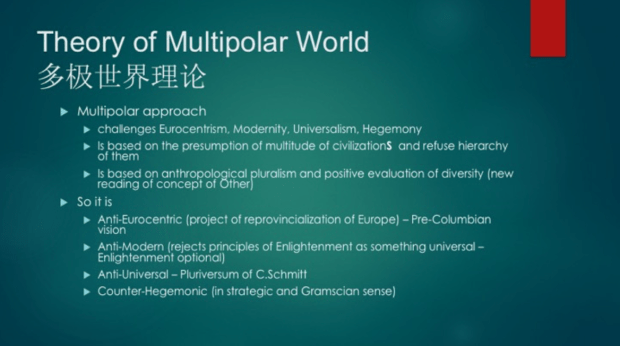

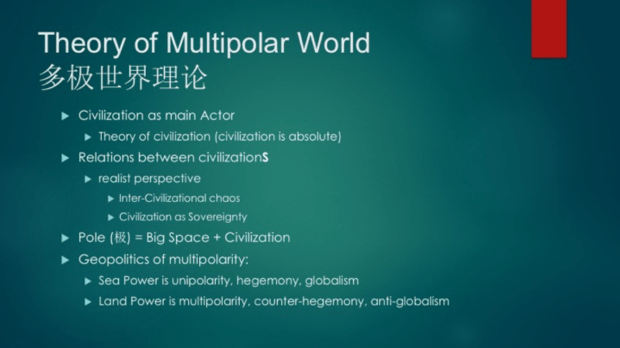

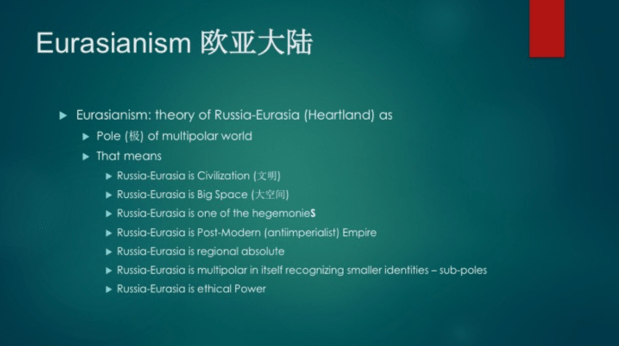

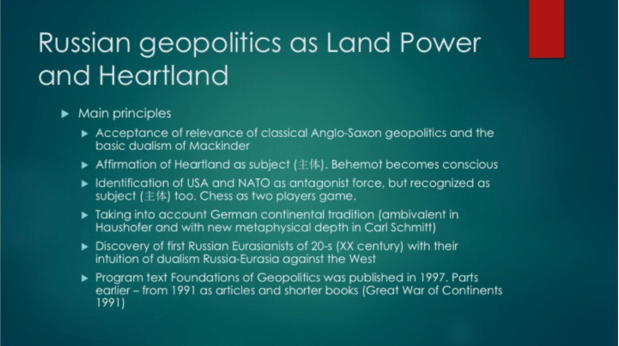

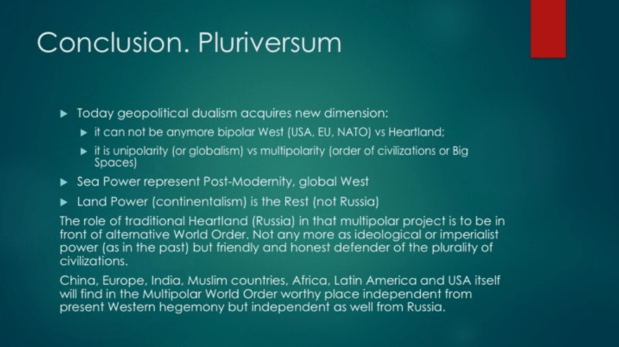

The theory of the multipolar world, mostly developed by us in Russia, by the Eurasianist school and Russian school of geopolitics, means acceptance of differences between civilizations. Civilization is the main actor in IR, not the state. The difference here is of huge importance. For example, if we develop Huntington’s idea and recognize that it is civilizations and big spaces that are the main actors, then we have a totally different vision of IR system which is not yet present in the manuals of IR. This is not only because it is at the first stage of development, but because it contradicts any kind of globalist, Western understanding.

What is civilization? Civilization is a relative absolute, or an aspect of the absolute. I would like to stress this. What does it meant to be an aspect of the absolute? It means to be absolutely absolute – but not alone. If you are fully, totally Chinese, you could understand something or someone who is not Chinese only if you have fulfilled this absolute dimension of identity. Then, from the center, not the outside, you can understand the Other. The only way to arrive at a real “globalization”, a real understanding of each other, is to start with ourselves. We cannot understand the Other if we do not understand ourselves. If we are not ourselves, we cannot deal properly with the Other. Then we would be only half Chinese, half Russian, half English, or half German. The real German should be based on the German Dasein (“Being-Here”), German Logos, German Tradition, German Identity. Only in the depth, core of this identity, can they understand others.

All problems are not in this deep realization of identity, but come when we start to pretend that we have already realized this identity, when we are only halfway along the path. People who enter a new religion are more radical and fanatic than people living in that religion for all their life. This is a kind of “too early” reaction. Nationalism, racism, xenophobia, the hatred of the Other, are possible only on the middle-path towards oneself. When we are arriving at ourself, we cannot be xenophobic, nationalist or racist. When we have fully realized our identity, our self, we are much more open to the other, because we consider, for example, that it is not only Russia that is absolute, but that by being more and more Russian, by discovering more and more the profound Russian identity, we are arriving towards the Absolute. Here, at that central point, we can meet the real, perfect, absolute Chinese. The Absolute Chinese meets Absolute Russian in the center of their civilization. We could compare Laozi or Confucius with Dostoyevsky or the Russian Orthodox Christian tradition. By realizing relative aspects of the absolute, we are coming to the meeting-point of civilizations – not outside, not being totally destroyed as a cultural unity and fragmented into individuals. Individuals cannot understand other individuals, because the pure individual is the most “primitive” form of being, totally limited to simplistic desires. The individual is like a robot, as a robot is a man without tradition or identity, a simulacrum of man.

Civilizations should be understood in the plural. There are Chinese, Russian, European, Islamic, African, Latin American, Western civilizations that can interact, peacefully coexist, try to exchange their identities. For example, to become Russian, you can come to Russia, learn our language, accept our values, if you want or you do not have to. This concept of civilization is therefore inclusive. But we cannot propose a single unique civilization for all of humanity. Maybe it will be the result of the Absolute, when everyone will go to the center of themselves, and we will arrive at the meeting-point of unique civilizations, but in order to do so we must make the long path within ourselves. That is the main meaning of the multipolar world.

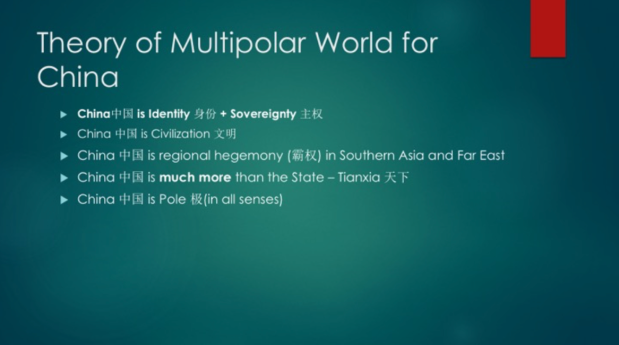

A pole is a Big Space + civilization, an idea + power, autarchy + sovereignty, hegemony + culture, force + authority. These are the formal concepts for understanding what a pole in the multipolar world theory is.

So, what could be the Chinese version of the multipolar world? This means the application of the same principles to China’s case. China is Identity + Sovereignty. If you stress sovereignty too much, you can lose identity, and if you stress only cultural identity, you could lose the practical capacity to defend your sovereignty. China should unite identity and sovereignty, and that is precisely what modern China is doing and what Xi Jinping wants to do. That is Greater China, the Chinese Dream.

China is a civilization, which must be affirmed. There is the danger that if you forget this, you will be treated as population, masses, and individuals. But you should educationally promote your civilization as such. You should call it a civilization.

China is a regional hegemony in South Asia and the Far East – and beyond, as long as your power, will, and capacity let you expand your hegemony. But such should be linked to your understanding of what is justice, what is balance. If you expand too much, you can overstretch your hegemony. Hegemony should be put in just limits. That was precisely our case. From time to time, Russia overstretched our empire and we couldn’t manage. We should expand only within the limit in which we can assimilate, rule, manage, as well as develop our relations with the people who join us – we should always give them something, not humiliate them. I think that is important in dealing with Xinjiang and Tibet now. You should have them under your control, but you should understand them as the Other and include them somehow. That demands always updating and adjusting.

China is much more than a state, and that is where Zhao Tingyang’s concept is of radical importance: affirming China as Tianxia. The growth of this Tianxia should be in harmony. You could say: let’s not start with the global, but start with our region, let’s install practically now the Belt and Road project, let’s install it here, demonstrate how it works, and if humanity will be seduced by this Tianxia moment, maybe others will accept it. The importance is to start with China within your possible capacities to introduce this inclusive concept based on relations, justice, ethics, and hegemony. China should be recognized as a pole in all senses. There you have already the basic aspects of a Chinese version of multipolar world theory.

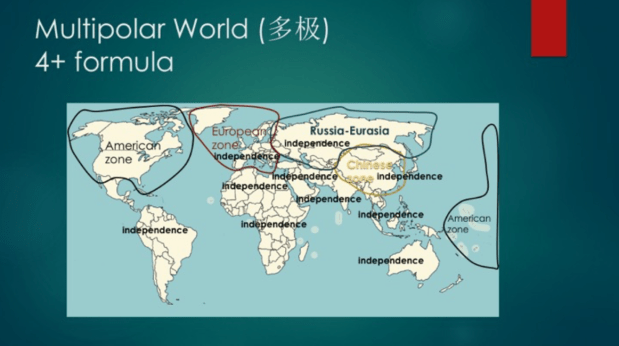

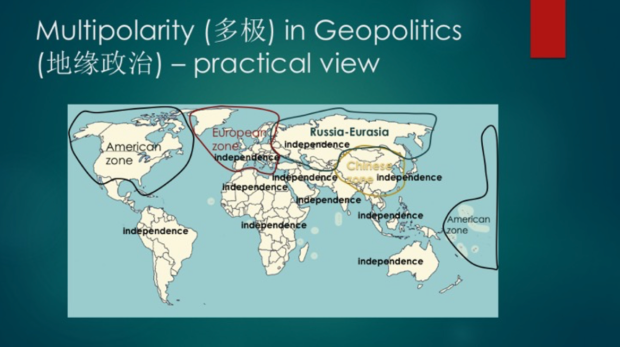

Here on this map we see the basic civilizations which could sooner or later be the poles of the multipolar world. Some of them are already present, such as the West, or European civilization if it will be affirmed as independent outside of globalist American hegemony, and there are the Eurasian, Chinese, and Islamic worlds – the latter of which is trying to affirm its identity, up to now not so successfully – and Africa. It is interesting that in South America multipolar thinking is very developed There are many theorists there, many partisans of multipolar world theory and South or Latin American identity.

Chinese International Relations theory can be based on multipolarity. In that sense, all the other factors that I have already mentioned can play an important role. Tianxia theory applied on an original scale could create this constant pole. The theory of moral realism of Yan Xuetong could be as well applied not only to China as a country, but Chinese civilization, and here his idea of ethics plus power acquires its implicit meaning. There are also analogues of the British school, with the relativization of Western rules for the club in which China is supposed to impose rules in the club that China would like to be a member of. In the present situation, the G7 is a Western club which imposes rules that are alien to Chinese culture. Here Zhang Weiwei and Qin Yaqing’s concepts can be very useful.

Here we can see a kind of beginning of the multipolar world in the form of 4+.

If China is on the side of Land Power, then the world order is already multipolar. We are not so far from multipolarity. If China chooses multipolarity, this is not necessarily an alliance with Russia. China could be Heartland herself, as Europe could be a continental Heartland as in classical geopolitics, and there is of course the Russian Heartland. These three heartlands could cooperate and create multipolarity very soon. This is an invitation to other civilizations as well.

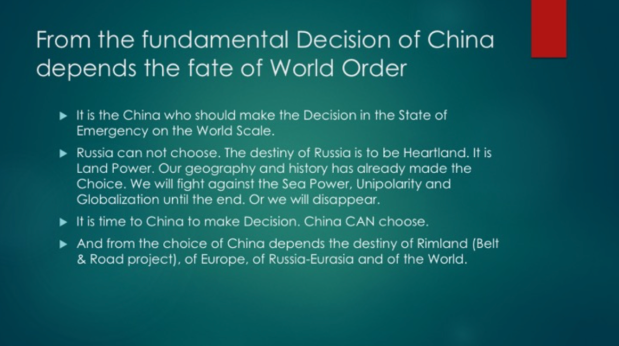

And so, to end, the geopolitical axiom of the 21st century is: Who controls China, controls Rimland; who controls Rimland, controls Heartland; who controls Heartland, rules the World.

We, Russia, cannot change our position in geopolitical space. We can exist as Eurasia, as Heartland, or we could not exist. We have no choice. It is difficult for Europe to make a choice in the present situation with the present elites. The only great power that in the present situation can make a choice, and has enough power to do so, is China. China has the choice as Rimland. Heartland cannot. America cannot, although it is trying to get out of this globalization and Sea Power with Trump – not Trump himself, but his words and the votes for him – the American people tried to get out of this globalist concept, to reaffirm themselves as an American pole, not global. That is a very good sign. But now it is really only China that can make the choice.

There are three solutions or choices for China.

China can be controlled by the US/NATO. That means that the West will rule Rimland, Heartland, and the World. If the globalists manage to promote their control over China through globalization, through influence on the young generation, technology, global capitalism, and liberal theories, they could rule the world.

In the old version of geopolitics, China could be controlled by Russia (Heartland). This is absolutely impossible today. It was not so impossible in Tsarist times, or including in Soviet times, when Stalin tried to help Mao and Russia influenced China. But today there is no way, will, desire, possibility, or resources to do so. We cannot control China. China is so huge and developed that this is out of the question. Our weakness is therefore a very good thing for multipolarity. If you logically, rationally no longer fear Russia, you are free to accept us not as a threat, but as an ally, not as asymmetrical as before. The Turks have understood this. The Turks from time to time still commit some errors, but as they they have come to understand that Russia is no longer a threat, they have become “pro-Russian” oriented on many things. It would be great if China would learn this lesson.

Finally, China could be controlled by China herself. In that sense, China should emphasize its Heartland identity, its traditional identity represented today by the Communist Party’s order in Chinese society.

If the choice will be made in favor of China, that will mean multipolarity. On the one hand, there is the West that proposes its own system of values, identity, and civilization, while on the other hand there is the Russian Heartland, which does not propose anything a-symmetric. Russia does not propose anything, except that China Become China Again and to Make China Great Again.

Footnotes:

[1] Daniel A. Bell, The China Model: Political Meritocracy and the Limits of Democracy, Princeton University Press, 2015.

[2] Graham Allison, “The Thucydides Trap: Are the U.S. and China Headed for War?”, The Atlantic (24/9/2015).

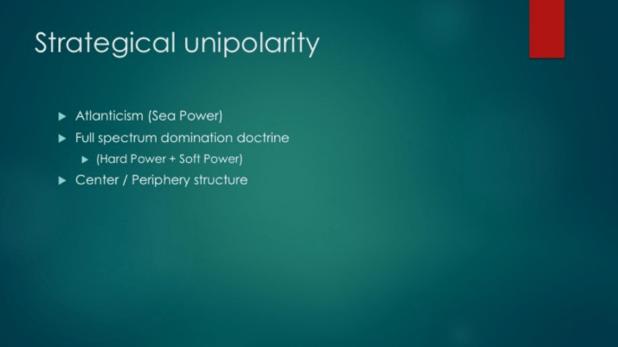

Unipolarity includes different aspects. For example, we could divide unipolarity into groups of concepts – open or “explicit”, and hidden, “secret”, or “implicit” unipolarity.

Unipolarity includes different aspects. For example, we could divide unipolarity into groups of concepts – open or “explicit”, and hidden, “secret”, or “implicit” unipolarity.  Strategic unipolarity includes Atlanticism, Sea Power in geopolitical terms, and full spectrum dominance doctrine, which affirms that in order to dominate the world totally, the West should not only use hard power or military power, but also soft power, culture, technology, network services, networks, and social services, that should control other societies from the inside, not only from the outside. That is the idea of full spectrum dominance – domination of the air, the cosmos, space, sea, land, and inside human brains. That is a project of controlling human behavior, psychology, being, and human minds, by coding them through different methodologies.

Strategic unipolarity includes Atlanticism, Sea Power in geopolitical terms, and full spectrum dominance doctrine, which affirms that in order to dominate the world totally, the West should not only use hard power or military power, but also soft power, culture, technology, network services, networks, and social services, that should control other societies from the inside, not only from the outside. That is the idea of full spectrum dominance – domination of the air, the cosmos, space, sea, land, and inside human brains. That is a project of controlling human behavior, psychology, being, and human minds, by coding them through different methodologies.

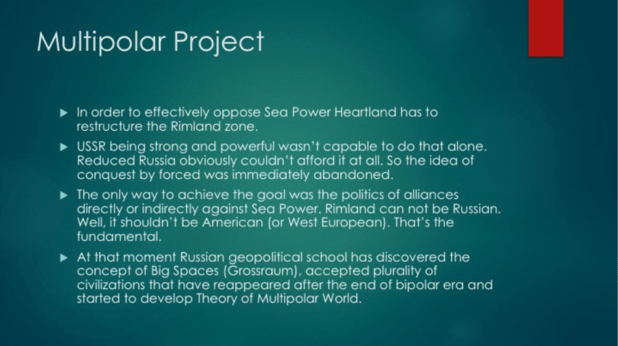

This state of things is more or less consciously understood by some academic groups in the world. We can call that the “multipolar world theory.” My own book in Russia, The Theory of the Multipolar World, which has been translated into French, is in the process of being published in English, and has been translated into Portuguese, Spanish, and other languages, presents this theory, and tries to put all of these elements that I have explained together.

This state of things is more or less consciously understood by some academic groups in the world. We can call that the “multipolar world theory.” My own book in Russia, The Theory of the Multipolar World, which has been translated into French, is in the process of being published in English, and has been translated into Portuguese, Spanish, and other languages, presents this theory, and tries to put all of these elements that I have explained together.

Here we can see civilizations corresponding more or less to Big Spaces and strategic analysis. Eurasianism and the Fourth Political Theory are a part of this.

Here we can see civilizations corresponding more or less to Big Spaces and strategic analysis. Eurasianism and the Fourth Political Theory are a part of this.

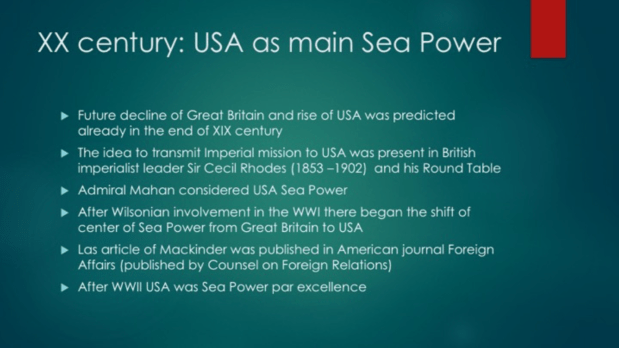

Very symbolically, Mackinder’s last article was published in an American journal, Foreign Affairs, whose editor’s organization, the Council on Foreign Relations, was created by the American elite just after the First World War in order to promote the Wilsonian vision of the United States as a global power operating in defense of capitalism, democracy, and so on. That was a theoretical, intellectual shift of the center of decision-making and the subject. This was a kind of transition of Sea Power. After that, Great Britain became the “old power”, the “senior”, “old man” tending his garden who offers some advice, but is not the real subject.

Very symbolically, Mackinder’s last article was published in an American journal, Foreign Affairs, whose editor’s organization, the Council on Foreign Relations, was created by the American elite just after the First World War in order to promote the Wilsonian vision of the United States as a global power operating in defense of capitalism, democracy, and so on. That was a theoretical, intellectual shift of the center of decision-making and the subject. This was a kind of transition of Sea Power. After that, Great Britain became the “old power”, the “senior”, “old man” tending his garden who offers some advice, but is not the real subject.

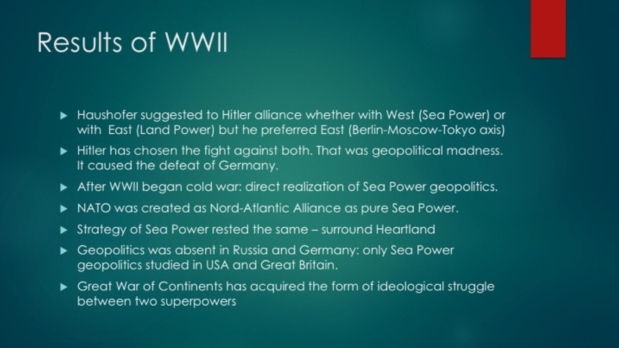

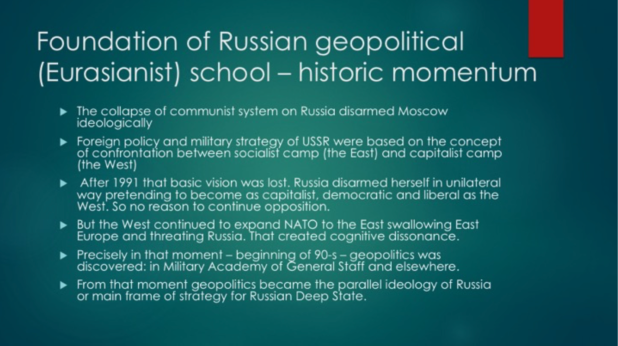

The result of the Second World War was that Hitler totally neglected Karl Haushofer’s advice. There was no more Germany, no more Hitler, no more National Socialism, because of the suicidal war that cost humanity many millions of victims. Just after the Second World War, the Cold War started, where there was again a pure illustration of the classic map of geopolitics. There was the Soviet camp, of which China was a part, the socialist camp, against the capitalist camp. There was a moment when the Soviet camp and communist, anti-capitalist countries acquired the geopolitical dimension of Behemoth. Communism was Behemothic in some ways. It was Land Power. That’s why communism won not in the industrial, liberal countries which had a big amount of proletarians, but in peasant, agrarian countries like Russia or China – because they were Land Powers. Communism won in Land Power, in the context of anti-liberal, anti-Western, anti-Sea Power. That is the geopolitical explanation of the Cold War.

The result of the Second World War was that Hitler totally neglected Karl Haushofer’s advice. There was no more Germany, no more Hitler, no more National Socialism, because of the suicidal war that cost humanity many millions of victims. Just after the Second World War, the Cold War started, where there was again a pure illustration of the classic map of geopolitics. There was the Soviet camp, of which China was a part, the socialist camp, against the capitalist camp. There was a moment when the Soviet camp and communist, anti-capitalist countries acquired the geopolitical dimension of Behemoth. Communism was Behemothic in some ways. It was Land Power. That’s why communism won not in the industrial, liberal countries which had a big amount of proletarians, but in peasant, agrarian countries like Russia or China – because they were Land Powers. Communism won in Land Power, in the context of anti-liberal, anti-Western, anti-Sea Power. That is the geopolitical explanation of the Cold War.

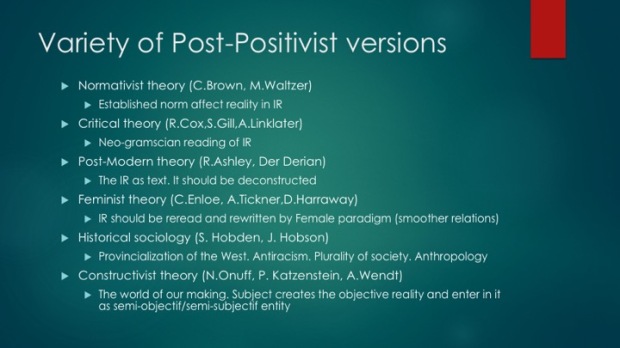

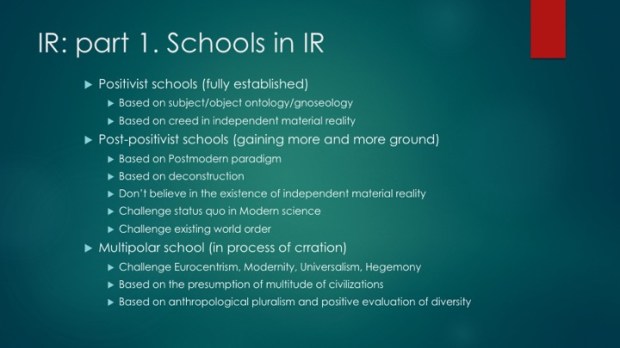

But the post-positivist schools are much more interesting in my opinion. There is the normativist theory that affirms that if we create a norm, then it does not reflect reality, but creates the reality, and everybody will follow the norm. If you try to punish people who violate some rule on the street, little by little this norm, which does not reflect anything, creates people who very carefully behave “correctly” because of these norms. By changing norms, we change reality – that is the modest version of post-positivism.

But the post-positivist schools are much more interesting in my opinion. There is the normativist theory that affirms that if we create a norm, then it does not reflect reality, but creates the reality, and everybody will follow the norm. If you try to punish people who violate some rule on the street, little by little this norm, which does not reflect anything, creates people who very carefully behave “correctly” because of these norms. By changing norms, we change reality – that is the modest version of post-positivism.